Survival Guide

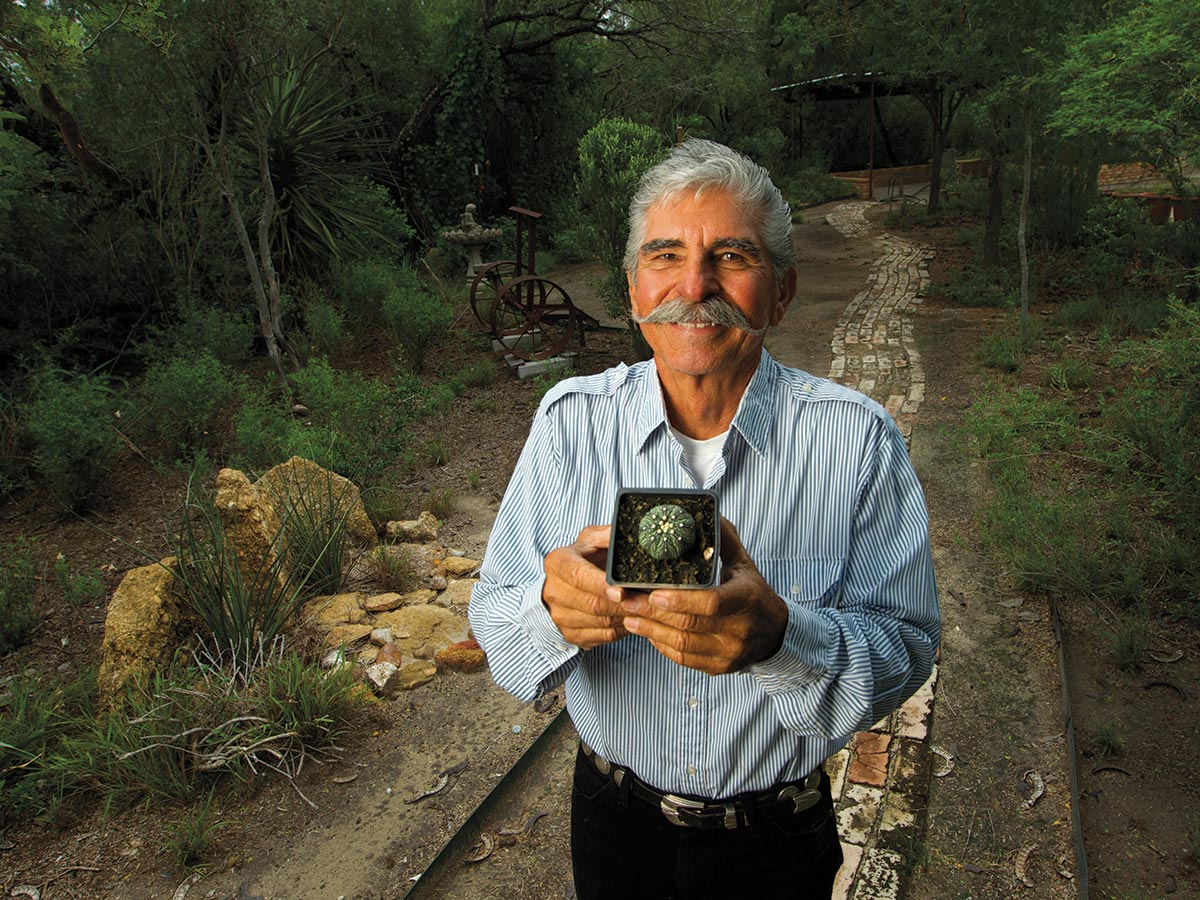

Benito Treviño proudly shows off a star cactus (Astrophytum asterias), one of the endangered species he’s propagated at Rancho Lomitas Native Plant Nursery. PHOTO Nathan Lambrecht

“HI, TONI … I THINK I’M LOST.”

I’m on a backroad near Rio Grande City, on the way to Rancho Lomitas, a native plant nursery and off-the-beaten-path, tiny eco-tourist oasis.

Toni, co-owner of Rancho Lomitas, has set me up to interview her husband and business partner, Benito Treviño, the following day. Toni handles most of the communications, manages the casitas (where guests can rent a room for a couple of nights or a couple of months), and gives cooking demonstrations with native plants on the weekends. Benito spends seven days a week tenderly tending to the nursery, giving tours focused on wild edibles and medicinal plants, and occasionally giving lectures or granting interviews to spread the word about native plant conservation.

“Let’s meet you in town and guide you in,” says Toni. “We just got a sudden thunderstorm with two inches of rain and it’s pretty intense out here.”

Driving down the fairly flooded and “wash-boardy” (Toni’s words) dirt roads under the dark sky with no street signs in sight, it is a comfort to watch the taillights of my hosts’ Outback as they forge through the rain ahead of me. When I arrive at the casita, I find homemade mesquite cookies and a container with mixed seeds, peanuts and marshmallows labeled “for the birds.”

In the morning, I scatter the seed and am quickly joined by scurrying scaled quails, white-winged doves and a chatty pack of Audubon’s orioles. Benito and I sit at a table overlooking this beautiful scene as he unintentionally carves hours out of his work day, lighting up like a proud father as he affectionately describes each species he’s raising at the 177- acre ranch.

KAH: What inspired you to start the nursery and ranch?

BT: I asked that question to myself when I was at UT. I didn’t know what I wanted to study and found myself taking a lot of botany. I always had [a] connection to plants since I was a little boy. I come from a large family — 15 of us, 13 survived — and my grandmother, aunt and mother would call me first if somebody had a headache or dysentery, send me out into the brush, and I would collect the plants. [My family] had a big influence on me because, as I was growing up and maturing, I appreciated how they managed to survive in this harsh climate using native plants. They found food, they found medicine, they found plants to make rope and fiber, to make teas for celebration — there were no stores here, and we couldn’t afford to buy things even if there were, so we were simply relying on native plants.

Foraging and utilizing native plants has become a bit of a trend in urban areas, but it sounds like it was a real way of life for you.

It was common knowledge; growing up here without it, [we] wouldn’t have survived. You know, I ask people my age, and very, very few people know anything of the native plants. Their parents knew it, their grandparents knew it, but they didn’t learn it. One of the things that inspired me to do tours is that I want the upcoming generation to be aware of how important our native plants are — not just because they are beautiful and you can use them for landscaping, but because there is a very deep history with native plants that made settling this part of the country possible.

How did you get started?

If I was looking at it financially, I would have started a nursery and said, “I’m going to grow lots of annuals, hanging plants, ‘cause that’s what the people want,” but for me it was not a financial thing, it was something in my heart that I wanted to do. [I thought] “This is probably a mistake, but I’m going to open a native plant nursery. If I don’t have sales, at least I will learn to germinate seeds, and it will be like a scientific study.” So I started with a tiny 8-by-10 greenhouse. I started growing, thinking, “I need sales, so I can keep things moving and have more space, so I’m going to start doing landscaping.” I started getting calls from schools to landscape with native plants. Financially, it was a much better model, but at one point I said, “I don’t want to be a landscaper. I want to grow native plants. I want to teach kids about the benefits of plants. I want to convince people not to plant invasive plants and tell them the benefits of native plants. There’s beauty, you can attract butterflies and birds.” That’s what I wanted.

Treviño aims to be a hero to endangered and threatened native plants; here, he tends to endangered Walker’s manioc (Manihot walkerae) in his nursery. PHOTO Nathan Lambrecht

So you turned away from success?

Yes! Many times! I grew 856,000 plants before I decided to shift over to growing my favorite plants. I decided to concentrate on bigger plants and sell to retail nurseries so the public has a choice between natives and non-natives, and then I would shift over to what I think is a greater priority with native plants, and that’s the threatened species and endangered species.

We have star cactus — you know we live in Starr county, but that’s just a coincidence. Years ago, there was one ranch in Starr County, out of the whole United States, that was known to have star cactus. They have been heavily poached. A rancher saved two from land that was going to be developed and gave them to me and Jim [Seeden, Rancho Lomitas’ resident naturalist]. As it happens, star cactus has complete flowers, anther and pistol and everything it needs, but it genetically cannot pollinate itself. Mine would bloom and Jim’s wouldn’t, and then his did and mine was not, so how could we cross pollinate? Now we have been freezing the pollen and have three different populations. I can see myself in five years having within the thousand range. I want to establish a star cactus population where I can really keep an eye on it, and then start giving them to U.S. Fish and Wildlife and Texas Parks and Wildlife for restoration.

I received a little package in the mail, I don’t know from who, which had Johnston’s frankenia seeds. It’s another endangered plant here in Starr County. I germinated them and have a few plants. I’ve had them about five years — and the other day they finally bloomed! It has been delisted from endangered [status], but it’s still a threatened species.

What will happen to the plants when they are mature?

With the threatened species … my intentions are to include those species in consultations for landscaping. I want threatened species and uncommon species to be like cenizo — one day everybody and their mother will have them in their backyard because I provided them and I managed to convince people to plant them. I can’t take care of them all myself, so I’ll have a homeowner over here and another over there and eventually we will have thousands of them and they will no longer be threatened.

What kind of wildlife do you see out here?

Within this ranch, only 177 acres, there are five or six different soil types, and with every soil type you get different vegetation that grows there. We have the indigo snake — a threatened species, the reticulate collared lizard … we have the Mexican burrowing toad. When we bought this ranch, I was walking around and saw 177 acres that can potentially represent 20,000 acres or 100,000 acres because of the different soil types. In such a little place we have such diversity — and then with the diversity comes the different critters.

Does the name “Rancho Lomitas” have a special meaning?

It’s got lomitas, little hills. Little hills produce an ecological system called a ramadero … a critical habitat that exists basically in Starr County and a little bit in Hidalgo County because it requires gentle hills and a very gentle slope from the hills to a river. These soils here have a lot of clay and the water doesn’t penetrate. At the ramadero, because it recharges the water table and penetrates very deep, in a week or two [after rain] there will be a bunch of flowering plants. Then those plants will produce seeds, the birds will eat the seeds, and they will replenish in here. The ramadero is like a bridge for all this land that has food … and habitat. They are very critical.

Learn more about Rancho Lomitas Native Plant Nursery at rancholomitas.com.