Befuddling Fruits

Like all living things, plants are driven to reproduce. For flowering plants, the product of sexual reproduction is a fruit — a mature ovary housing one or more seeds. A seed is a plant in embryo waiting to grow into an adult plant. First, it must be dispersed to a suitable location and kept protected in the meantime. This is the role of the fruit.

Just as plants differ wildly in form and function, so do their fruits. This is due, in part, to their accessories. A true fruit consists of the ovary wall and the seeds inside; however, some fruits find themselves inside of or attached to other flower parts. These “accessories” aide in protecting and dispersing the seeds.

Fruits can be simple or compound, fleshy or dry. Simple fruits are formed either from a single ovary or fused ovaries of a single flower. Compound fruits are formed from several separate ovaries in a single flower, such as raspberries, or from multiple flowers, such as mulberries and pineapples.

Fleshy Fruits

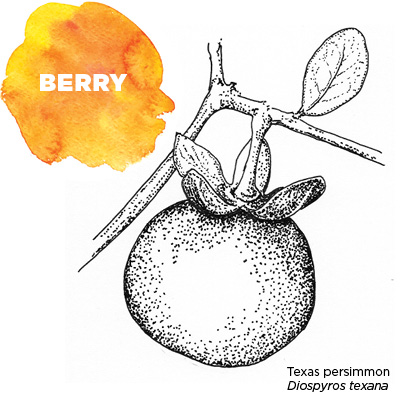

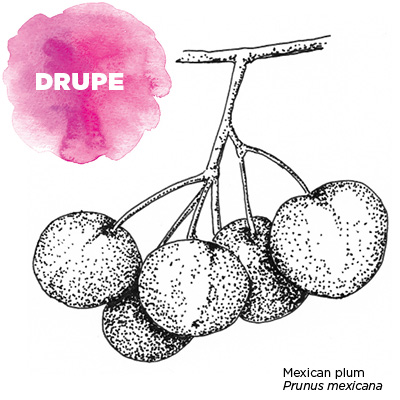

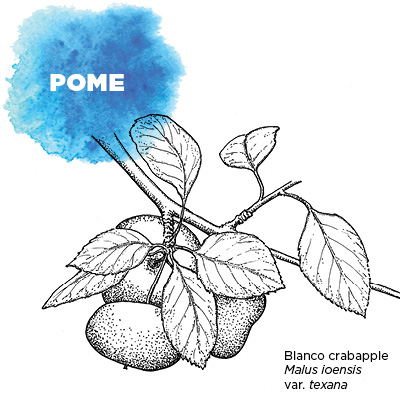

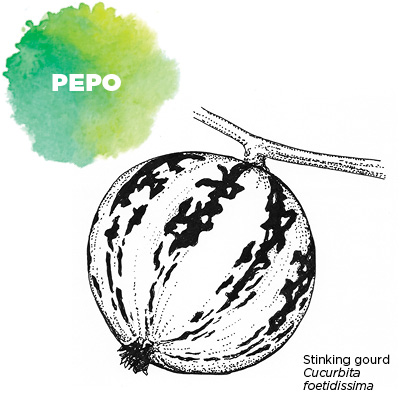

Plants with fleshy fruits generally rely on animals to disperse their seeds. These types of fruits are the most recognizable to us because, like other animals, we enjoy eating many of them. Fleshy fruits can be organized into three main types: berries, drupes and pomes.

In berries, all parts of the fruit are soft, and seeds are found distributed throughout the “flesh.” Examples include blueberries, cranberries and tomatoes.

Drupes, commonly called stone fruits, have a fleshy outer layer but a thickened, “stony” inner layer that contains the seed. Plums, apricots and peaches are drupes.

Pomes, like drupes, also have a fleshy outer layer surrounding a tougher inner layer, but in this case, the inner layer is papery or leathery. Pomes include apples, crabapples and pears.

Two additional types of fleshy fruits are pepos (cucumbers, squash, pumpkins) and hesperidia (some citrus fruits). Both are considered modified berries because the seeds are found throughout the flesh of the fruit; however, their outer layers are tough or leathery.

Dry Fruits

Dry fruits can be either dehiscent or indehiscent. The outer walls of dehiscent fruits break open (or dehisce) when mature to disperse the seeds. Indehiscent fruits remain sealed; since they don’t split open when mature, they rely on decomposition or some other outside force to release their seeds.

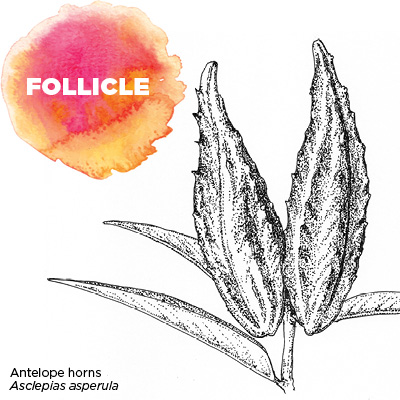

Follicles and legumes are dehiscent fruits. They differ mainly in the way they split open when dried. Follicles split along a single seam. Milkweeds, columbines and peonies all produce follicles.

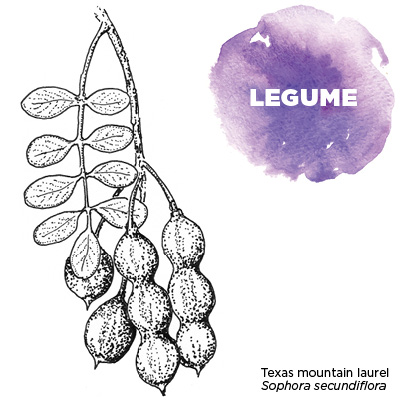

Legumes split along two seams and are the characteristic fruit of the pea and bean family, Fabaceae.

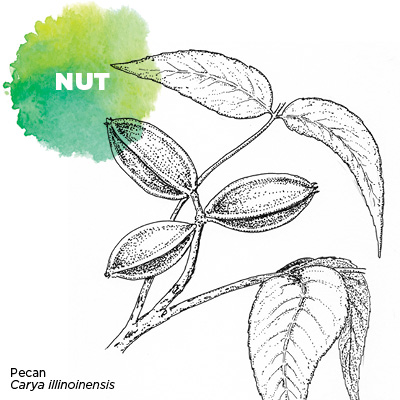

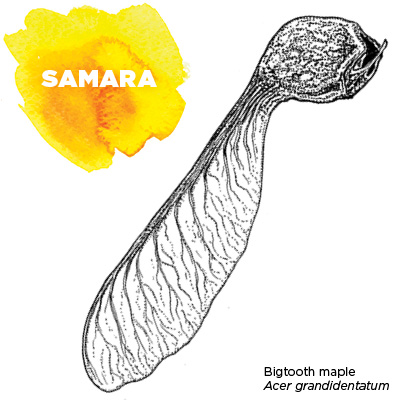

Nuts, achenes and samaras are indehiscent fruits. Nuts are distinguished by their thick, durable outer walls. Acorns, the fruits of oaks, are an obvious example.

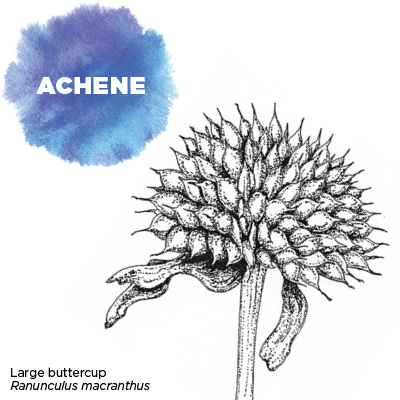

Achenes have a more pliable, thin outer layer and sometimes include a fuzzy, whiplike tail that allows them to float on the wind. (Fruits of the aster family, Asteraceae, are similar but topped with a “pappus,” the umbrellalike fluff that disperses dandelion seeds when you blow on them.)

Samaras (what some call “helicopters”) are the fruit type of maples and elms; they are similar to achenes but have winglike attachments that aid in wind dispersal.

Fruits and the flowers that produce them are key to identifying plants. Learning the names of fruits and the plants they are attached to can help us feel closer to nature and more appreciative of our native flora. Fruits are also an essential part of the food web, keeping countless species of animals fed, including humans. The next time you stop and admire the flowers, look a bit further and consider the fruits that are sure to follow.

Daniel Murphy is collections curator at Idaho Botanical Garden and founder of Awkward Botany, a weekly science blog. He specializes in native and waterwise plants and is working on a book about the world’s most hated plant group: weeds.

ILLUSTRATIONS Collene Sweeney