Born to Rock

It’s a bluebird day in early spring — so sunny, so breezy, so pinch-me picturesque, it’s almost impossible to believe a withering blanket of heat will soon smother this landscape.

But as all Texans know, summer always comes, even to Austin’s idyllic Bull Creek District Park, with its limestone slabs and emerald green swimming hole. Less than 10 miles north of the capitol building, this hidden gem is a far cry from the movie-set deserts of West Texas. And yet, for the resident plant communities carving out a hardscrabble existence here, it’s an equally extreme environment, for two big reasons: One, rock absorbs heat, so when it’s high noon in high summer, this limestone bonanza will be baking. Two, even on a mild March day, there may be limestone and water, but there’s not much in the way of soil. And if you’re a plant, soil is your breakfast, lunch and dinner.

For most plants, that is. Not for lithophiles, a motley crew of flinty, weather-beaten vegetation that settles in the cracks, crevices, potholes and bare cliffs of rock; dirt be damned. These varieties don’t really need soil, and they’ve evolved to withstand blistering temperatures. They’re tough — Texas tough. Some of them also just happen to be miniature, but don’t make the mistake of calling them cute. Botanists Dr. Karen Clary and Bill Carr prefer “charismatic microflora,” a playful term honoring the miniature scale that allows many of these blink-and-you’ll-miss-them varieties to survive.

Clary, Carr and I have synchronized our watches and convened here, at Bull Creek, to see if we can spot some scrappy native plants hanging out on the ample limestone. Because lithophiles are opportunistic sprouters, squatting in any chink where conditions are tolerable, we don’t have a map, but we do have drinking water, hiking boots and a healthy respect for botanical tenacity.

Though comfortably upright in this image, rock daisy has envious grappling skills; it’s been known to live upside down on rock faces to avoid being eaten by hungry goats and deer. PHOTO Sally and Andy Wasowski

Tough Customers

How do you know what’s a lithophile and what isn’t? For starters, not all rock dwellers are tiny. Some varieties of agave and yucca are stop-in-your-tracks stunners, larger-than-life beauties you couldn’t overlook if you tried. So, size doesn’t matter.

Neither does scientific classification, geographic location or type of rock. Some lithophiles live only on rock. Other shapeshifters take up residence on rock, gravel, sand, shallow deposits of junk soil, you name it. Some are Texas natives. Some are endemics, meaning they don’t grow naturally anywhere else. And some are invasive species.

In fact, “lithophile” isn’t a taxonomic genus or family. It’s more like a mindset. The common characteristic these plants share is in their nickname: “litho,” for “rock,” and “phile,” meaning “lover.” Over millennia, these rock-loving flora have evolved and adapted to thrive in and on rock, from the karstic limestone of the Llano Uplift to the basalt of Big Bend.

FROM LEFT Wright’s cliffbrake fern doesn’t bother with flowers; rather, it reproduces via spores. Ovateleaf cliffbrake does the same and is found only on the rocky slopes and ledges of Texas’ Edwards Plateau and Trans-Pecos regions. PHOTOS Alan Cressler, Joseph Marcus

Lithophiles aren’t into luxury. Besides setting up camp on the hardest of surfaces, they’ve learned to withstand the harshest of climates (see: anywhere in Texas in August). Some use size as their secret weapon, as in the case of the charismatic microflora. By staying itsy-bitsy, they’re able to concentrate whatever precious resources they manage to grab. “Lots of plants in this area are very energy conserving,” says Clary, the former director of conservation at the Wildflower Center. “They’re just big enough to reproduce, to flower, to attract pollinators, to fruit” — and no bigger.

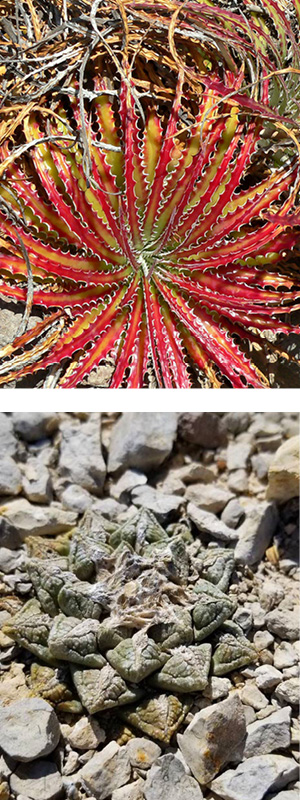

TOP Guapilla, also known as Texas false agave, thrives in deserts but can also work as an accent plant in a xeric home garden. PHOTO Stan Shebs (CC BY-SA 3.0) BOTTOM Camouflage master living rock cactus has spongelike stems that shrink and become less and less visible as conditions dry out (making it almost indiscernible from surrounding rocks at times.

PHOTO Adam Black

Others are ascetics, living a monastic life on an extremely spartan diet. “For a lot of the rock lovers, their metabolism is totally different [from typical plants],” Clary explains. “They don’t need the level of nutrients that soil provides. They’ve figured out a way to get what they need without having full plates. Their menu is very, very small.”

How do they make that work? “By conserving water,” says Clary. “By not growing very fast. By changing shape.” In other words, by being wily, a skill familiar to lizards and coyotes and other desert dwellers that scrape by in challenging climates. The ability to go with the flow, to shift and adapt, lets them make a home where others couldn’t.

In Central Texas, certain lithophiles have learned to pitch their metaphoric tents on cliff faces and to suspend themselves upside down from rocky overhangs. Take rock daisy (Perityle lindheimeri), which hangs off the rocks at Hamilton Pool. The region has long been a hotbed for raising goats and, more recently, for runaway populations of deer. Choosing a gravity-defying homestead gives rock daisy a refuge since, as Carr points out, “You don’t see a lot of deer climbing cliffs.”

Southern maidenhair fern (Adiantum capillus-veneris), in abundance at Bull Creek, has cornered its own real estate market. Rainwater percolating down through crevices in the vertical limestone eventually hits an impenetrable layer of rock, at which point it runs laterally. Voilà: a half-inch-wide shelf of home sweet home too narrow for other would-be colonizers.

And then there’s guapilla (Hechtia texensis), one of Clary’s personal favorites, with a rugged moptop of leaves that could pass for a pineapple. Also like pineapples, guapilla comes from the bromeliad family of mostly tropical plants. So what’s it doing growing in the limestone terraces and gravel flats of Big Bend? “Most plants sweat a lot, but desert plants that grow on rocks don’t do that,” Clary says. They save up every little bit of moisture they can, and, instead of respiring 24 hours a day, they lean nocturnal. Like joggers who time their workouts after dusk, “They breathe [most] at night.”

Another is living rock cactus (Ariocarpus fissuratus), a Big Bend species whose dormant appearance Clary likens to a dead sponge. But when it blooms, boy howdy! “It has the most gorgeous purple flowers,” she says. “We call it facultative,” meaning it blooms when it can (in this case, after rain). It’s just biding its time.

A West Texas Mindset

Guapilla and living rock cactus are Far West Texas endemics, found nowhere else on the planet. In fact, Big Bend is a veritable rock garden, with some endemic and many native lithophiles.

Now retired, Patty Manning was the longtime greenhouse manager at Sul Ross State University in Alpine, Texas. When I reach her on the phone to talk lithophiles, she wanders into her backyard greenhouse, a much less state-of-the-art affair than her former domain, she assures me, but what sounds like heaven for rock-loving plants and their appreciators.

Manning is unabashedly pro-charismatic microflora. Although she’s surrounded by attention-grabbing desert beauties, the lithophile closest to her heart is purple scaly-stem (Elytraria imbricata). “It’s actually kind of a weed in Mexico,” she says, laughing. “It’s a very small plant that grows in cracks on cliff faces. You find it in really harsh areas where you wouldn’t expect to see something that delicate. I like it because it has a really small, really beautiful, really tiny little flower. It’s not showy. It’s just pretty.”

FROM LEFT Desert savior, sand spikemoss and resurrection plant. PHOTOS (left) Sean Watson, (other two) Alan Cressler

Other lithophiles to look for in the Trans-Pecos include two melodramatically named varieties. First, there’s resurrection plant (Selaginella pilifera), which, most of the year, you might mistake for a clump of dead leaf litter. But when rare rain comes, the fern goes through a time-lapse lifecycle: rehydrating, producing spores, reproducing and then returning to dormancy in a matter of days. And then there’s desert savior (Echeveria strictiflora), the only echeveria that grows native outside of Mexico.

I ask Manning why so many of us are gaga for echeverias, a genus of lithophilic succulents beloved by houseplant Instagrammers everywhere. Is it because their juicy little pads are almost — well, fleshy? “I think it’s sort of that anthropomorphic thing,” she says. “But they’re also pretty forgiving. Of course, anyone who has grown succulents knows they’re not foolproof. You do have to pay attention. You can’t water them too much. But they root pretty easily.”

Is the ability to adapt, to get by in austere environments, something lithophiles have in common with, say, the residents of Far West Texas? Manning laughs again. “I don’t know that I’m tougher than anybody else. But I can certainly live without a lot of resources.”

Cliff Notes

Back at Bull Creek, Carr lifts the brim of his circular sunhat to get a better look at the cliff face rising above us. “This is all Cretaceous, 65 to 100 million years old,” he says. “Most is Edwards Limestone, but you’ve got bands of Glen Rose and marl — crumbly limestone that erodes faster than the layers on top of it. The plants grow out of those layers.”

Carr will be the first to tell you he’s no geologist, but as a field botanist specializing in landscape inventories for the likes of Texas Parks and Wildlife and The Nature Conservancy, as well as for private clients via his own firm, Acme Botanical Services, he knows a thing or two about rock. Just over the hill, he explains, is a major fault zone, the Balcones Escarpment. And on the other side, underneath Austin, is much younger rock: the eponymous Austin chalk, as well as lots of geologic material that never consolidated. Meanwhile, over at Enchanted Rock, there’s one kind of granite, called Town Mountain, and a little further northwest, at Inks Lake State Park, there’s another, called Valley Spring Gneiss.

“You look at a geologic map of Texas and northern Mexico, and you’ve essentially got an island of limestone surrounded by things that aren’t limestone,” Carr says. “It got isolated.” In order to survive the desert island experience, plants began to eye their siblings. “There was not a whole lot of gene flow,” Carr says. “Things got closely related after a while.”

Just down the road, however, you might find an entirely unique plant family — a whole other gene pool, if you will. A few years back, Carr was conducting simultaneous plant inventories of Government Canyon State Natural Area, near Helotes, Texas, and Bastrop State Park, 100 miles away. He found more than 500 plant species in each park, but only about 18 percent of those were shared between the two. That’s like almost nobody moving from San Antonio to Austin for millions of years.

FROM LEFT Bluntlobe cliff fern, purple scaly-stem, and Bill Carr investigating a rock face at Bull Creek District Park. PHOTOS Wynn Anderson (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), Alan Cressler, Jennifer Wehunt

Soil chemistry might explain the neighboring tribes. Bastrop is neutral or slightly acidic, while the greater Llano Uplift is moderately alkaline. “These two parks, they’re like next-door neighbors, practically, but they have almost nothing in common,” he says. “It happens all over the world, different things growing on different substrates. But it’s cool that we live in a place where that happens right next to each other, where we can see it.

“That’s why I’m saying Texas is the best place to be as a botanist,” Carr continues. “We’ve got 513 endemic [plant] species”— maybe 50 to 75, he estimates, in Central Texas alone. “Talk about a good reason to conserve: These plants don’t grow anywhere else.”

Small Packages

Led by Carr and Clary, I’ve seen a veritable field guide of native Texas lithophiles (at Bull Creek as well as Inks Lake State Park): Lindheimer’s silktassle (Garrya ovata ssp. lindheimeri), evergreen sumac (Rhus virens), twistleaf yucca (Yucca rupicola), yellow stonecrop (Sedum nuttallianum), sand spikemoss (Selaginella arenicola), lace hedgehog cactus (Echinocereus reichenbachii), water pygmyweed (Crassula aquatica), two kinds of cliffbrake fern (Pellaea wrightiana and P. ovata), bluntlobe cliff fern (Woodsia obtusa), Wright’s lip fern (Cheilanthes wrightii) and rock quillwort (Isoetes lithophila).

We’ve foraged our way through a moveable feast of pepperweed (Lepidium densiflorum), cucumber plant (Parietaria pensylvanica), prickly pear tuna (Opuntia engelmannii) and who knows what kinds of wild onions. We’ve talked native habitats, both plant and human (Carr, Ohio; Clary, Panama; me, Texas). And I’ve heard Carr hold numerous friendly, if one-sided, conversations with plants (“You blooming yet, buddy?”).

But the thing I’ve heard most often, from Carr and Clary and Manning alike, is: “How? How did they get here?” Because as much as we know about lithophiles and the botanical science of what and where they grow, we don’t really know how they ended up where they did or didn’t.

Perhaps no plant we come across underscores this serendipity more than our last find of the day at Bull Creek. After fording the stream, we’re squelching our way along the east bank, following a footpath that veers to and fro in the shadow of the cliff wall. We’ve just passed a smattering of invasive species, suburban yard plants deposited here by way of bird diet. I’m spacing out in the dappled sunshine, soaking up the sensations of spring, when I hear a squeal of delight.

It’s heart-stoppingly beautiful, like someone took an ethereal tulip and shrank it down to dollhouse scale. Talk about charismatic microflora.

Up ahead, Clary and Carr are huddled around a pockmarked limestone outcropping. Tender green shoots, each with a tutu of leaves encircling its midsection, sprout from cavities in the rock. Atop every stem is a tiny white flower, smaller than a pinkie fingernail but, with the sun catching it just so, absolutely luminescent against the shadowy rock. If I was here by myself, I would have missed it or dismissed it as another weed. But today, it’s heart-stoppingly beautiful, like someone took an ethereal tulip and shrank it down to dollhouse scale. Talk about charismatic microflora.

It’s thimbleweed, Anemone edwardsiana — as in the Edwards Plateau, the endemic homeland of this lithophilic buttercup, often found in shaded canyons (check), especially along limestone ledges (check), at the bases of bluffs (check). “It’s only out this time of year,” Clary says. “Its window is really, really short. If you were here in another week, you wouldn’t see it.”

Whether our timing is fate or Mother Nature or luck of the draw, I’ll take it. Turns out how doesn’t much matter when the what is so marvelous.

Jennifer Wehunt is the former editorial director of the Appalachian Mountain Club; she specializes in stories of how the environment impacts society and vice versa. Read more at texpatatlarge.com.