Natural Accents

Gardeners and plant enthusiasts have long turned to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Plant Hardiness Zone Map as a tool for planning landscapes, selecting plant material and understanding local conditions. But there’s a different tool that offers richer knowledge and detail of natural diversity in Texas and beyond: ecoregions.

Imagine a gardener who is moving from Houston to San Antonio; in planning their new garden, our hypothetical plant-lover checks the USDA map — which is based simply on average winter low temperatures — and discovers both places are in Zone 9a. Relieved, our gardener decides to plant some Houston favorites, including azaleas (Rhododendron spp.) and longspur columbine (Aquilegia longissima). Not so fast …

The two areas are in the same Plant Hardiness Zone but very different ecoregions, or natural zones. Houston lies in the uber-humid belt where the South Central Plains ecoregion (or Piney Woods) meets the Western Gulf Coastal Plain ecoregion, an area that receives 50-plus inches of rain a year and is home to tropical roseate spoonbills, bald cypress swamps and salt marshes. San Antonio sits on the margin between two prairie ecoregions and the semi-arid Southern Texas Plains, where rainfall can easily be half of that in Houston, soils range from alkaline to deep clay and tornadoes are more likely than hurricanes. From a plant’s point of view, “It’s a whole different world,” says botanist Bill Carr, an expert on Texas ecoregions.

Think of ecoregions as the high-resolution view of landscapes.

WHAT IS AN ECOREGION?

An ecoregion is a geographically distinct area characterized not by political borders or average temperatures but by a much more sophisticated assemblage of traits. Those traits include similar landforms and geology, substrate and soil type, climate and precipitation, evolutionary history, and complex biological relationships between everything from soil bacteria and invasive species to iconic native flora and fauna. Think of ecoregions as the high-resolution view of landscapes: They capture the fine details, including a host of factors critical to whether or not plants will thrive in an area.

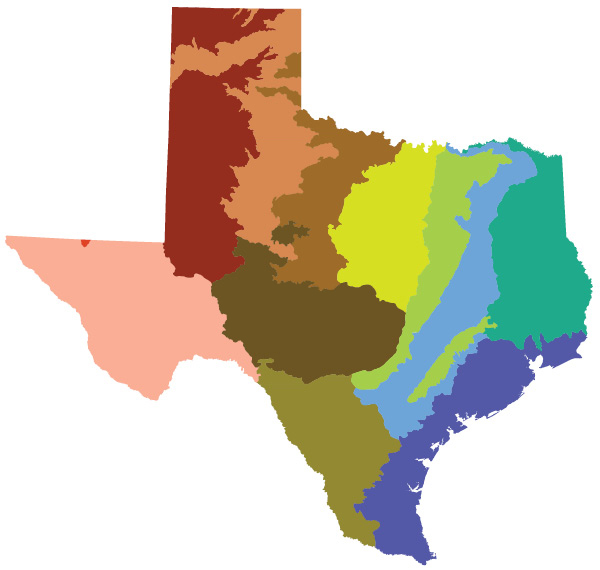

Understanding those factors is especially critical in Texas because the nation’s second-largest state embraces a staggering amount of natural diversity. Take annual rainfall: From east to west, Texas spans a range from up to 56 inches per year in the Piney Woods (officially the South Central Plains) to less than 12 inches per year in the arid Chihuahuan Desert ecoregion — most of which evaporates immediately into the pore-puckeringly dry air. These extremes make for a wide range of environments: Gulf Coast barrier islands and plains, tall- and shortgrass prairies, pine forests, oak woodlands, sub- tropical scrublands, cool mountain “islands,” and miles of sparse desert. Ecoregions (which are defined by the Environmental Protection Agency) help to illuminate Texas’ diverse nature.

Those described here, Level III, are commonly used by scientists — but they can also be of use to gardeners, naturalists and anyone interested in better understanding the landscapes where they live. Ecoregions express the particularities of nature in any area, the distinct “language” of place, as Lady Bird Johnson put it. When she said, “I like it when the land speaks … in its own regional accent,” she could have been talking about ecoregions. Because if Texas is a language, ecoregions are its local accents — the complex nuances that distinguish its parts.

TEXAS’ TWELVE LEVEL III ECOREGIONS

Torrey yucca (Yucca torreyi) graces the rugged terrain of the Chihuahuan Desert ecoregion with blossoms painted from the same palette as the land itself. PHOTO Laurence Parent

Chihuahuan Desert

Chihuahuan Desert

Covering most of Texas west of the Pecos River, the Chihuahuan Desert ecoregion (known to many as the Trans-Pecos) is a vast expanse of arid grass- and shrubland dominated by creosote bush (Larrea tridentata) and tall yuccas, a landscape that, to many, appears desolate. “As far as the eye can reach stretches one unbroken waste, barren, wild, and worthless,” wrote John R. Bartlett, Commissioner of the first U.S.-Mexico Boundary Survey in 1851. Yet this high-elevation desert and its small mountain ranges support a surprising diversity of plants, particularly native shrubs and cacti. “One of the special things about the Chihuahuan Desert is that we have so many fall bloomers in response to the summer monsoon,” says Patty Manning, a botanist retired from Sul Ross State University in Alpine, Texas, “which makes late summer and fall great times for plant-hikes.” Although this ecoregion contains two of Texas’ major rivers — the Rio Grande and the Pecos — it is a land of little water, averaging 7 to 12 inches of precipitation annually. Rare springs and perennial streams support an abundance of wildlife and endemic plants including Hinckley’s columbine (Aquilegia chrysantha var. hinckleyana).

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: lechuguilla (Agave lechuguilla), scarlet bouvardia (Bouvardia ternifolia)

VISIT: Big Bend Ranch State Park

PLANT LIST »

Arizona/New Mexico Mountains

Arizona/New Mexico Mountains

This ecoregion is Texas’ smallest, encompassing what biologist Fred Gehlbach called the “mountain islands” of Guadalupe Mountains National Park, which rise like mirages out of “desert seas” in far West Texas. Gelbach’s description evokes the isolation of the Southwest’s small mountain ranges with their cool temperatures and relatively lush vegetation surrounded by miles of desert basins. This ecoregion includes the state’s highest point, 8,751-foot-high Guadalupe Peak, a jutting remnant of an enormous reef from a long-vanished ocean. With high elevation comes cooler temperatures and increased precipitation (20 inches instead of just over 7 at the base of the mountains), which nurture forests of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) — evoking the distant Rocky Mountains. Ribbons of riparian plants and deciduous trees including bigtooth maple (Acer grandidentatum) and velvet ash (Fraxinus velutina) find shelter in stream-made canyons, their leaves aflame in scarlet, orange and lemon yellow come fall.

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: ponderosa pine, stream orchid (Epipactis gigantea)

VISIT: Guadalupe Mountains National Park

PLANT LIST »

American basket-flower (Centaurea americana) blankets a field near Lubbock in the High Plains ecoregion. PHOTO Esther Irish

High Plains

High Plains

If there were a title for Texas’ flattest landscape, this ecoregion would win. Unlike the Southwestern Tablelands ecoregion to the east or the Chihuahuan Desert to the south, the High Plains ecoregion lacks rivers large enough to carve into its sedimentary rock layers, resulting in a tablelike and windswept expanse of shortgrass prairie. Spanish explorers dubbed the region, which covers the western two-thirds of the Texas Panhandle, “el Llano Estacado,” which means “the Staked Plain,” perhaps for wooden stakes driven into the ground as landmarks. Despite its soporific flatness and irrigated cropland replacing much of the original grama and buffalo grasses (Bouteloua spp. and B. dactyloides, respectively), this ecoregion is high in biodiversity, including huge numbers of migratory waterfowl, from ducks and geese to shorebirds, drawn to the region’s 20,000-some playas, seasonal lakes created by winter snowmelt and summer rains. The wonders of the High Plains require slowing down, as author, artist and Texas Tech professor Susan Tomlinson writes: “The landscape is so big that we can’t focus on it; we have to steady ourselves by looking at the small things, like wildflowers, and thorns, and coyote tracks.”

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: sideoats grama (B. curtipendula), plains yucca (Yucca campestris)

VISIT: Lubbock Lake Landmark

PLANT LIST »

Southwestern Tablelands

Southwestern Tablelands

Rivers cutting into the hard caprock along the east margin of the High Plains ecoregion carve canyons tinted rusty red and pink, the colors of the softer formations beneath. Artist Georgia O’Keefe, who briefly taught school in Canyon, Texas, described the charms of the canyon country when she wrote about Palo Duro Canyon, “It was colorful — like a small Grand Canyon. There were sharp, high edges between long, soft earth banks so steep that you couldn’t see the bottom … it was a lone place.” The headwaters of three major Texas rivers— the Red, Brazos and Colorado — lie in this ecoregion, which encompasses roughly the eastern third of the Panhandle, from the western border of Oklahoma south to the northwestern edge of the Edwards Plateau. With annual precipitation of 20 to 24 inches, slightly greater than the High Plains, the canyons, mesas and rolling hills of the Southwestern Tablelands ecoregion support a mosaic of juniper-oak woodlands, prairie ranging from shortgrass on exposed mesas to pockets of tallgrass in sheltered bottoms, and unique wildlife including the endemic Palo Duro mouse and the Texas horned lizard (both threatened species). Sandbars along the braided river channels provide nesting habitat for the interior least tern and endangered snowy plover.

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: Havard oak (Quercus havardii), redberry juniper (Juniperus pinchotii)

VISIT: Palo Duro Canyon State Park

PLANT LIST »

Central Great Plains

Central Great Plains

The lower, more rolling country of the Central Great Plains ecoregion east of the Southwestern Tablelands receives more precipitation (24 to 28 inches a year) and was once largely midgrass prairie maintained by bison, prairie dogs (which graze shrub and tree roots) and periodic fire. When those influences were removed, woody shrubs such as native mesquite (Prosopis spp.) and Ashe juniper (Juniperus ashei) prospered, turning the prairie into a wooded savanna and altering both soil formation and stream flow (woody shrubs not only intercept more rainwater, they “drink” more from the soil, resulting in less to recharge streams, river and aquifers). Much of this ecoregion is now cropland; leaching from saline shales below the surface can leave a white crust on the soil and contributes to high salinity levels in some streams.

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Texas poppymallow (Callirhoe scabriuscula)

VISIT: River Bend Nature Center

PLANT LIST »

Waterways lined with stunning bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) join bats and limestone caves as hallmarks of the Edwards Plateau ecoregion. PHOTO Laurence Parent

Edwards Plateau

Edwards Plateau

Stretching east from the Pecos River to Austin, the Edwards Plateau ecoregion is an island of its own, a broad tableland formed of thick limestone layers, entirely unlike the surrounding landscape. Stream drainages running off the plateau have cut winding canyons and dissolved limestone to form underground caves, creating sheltered habitat for unique species including the golden-cheeked warbler, Texas blind salamander, Balcones ghostsnail and Mexican free-tailed bat. The bats, perhaps the Plateau’s most well-known wildlife, roost in caves by the millions; their nightly feeding flights provide a viewing spectacle for tourists and millions of dollars in pest-control services to area farmers. This ecoregion’s canyons are also “a huge hot spot” for plants, says botanist Bill Carr, sheltering 75 plant species found nowhere else in the world. One of those, a graceful shrub with drooping white flowers called Texas snowbells (Styrax platanifolius ssp. texanus) is endangered. Although the area’s riparian habitats are threatened by overgrazing, contemporary dewatering of streams and exploding land development, many endemic plant species once thought endangered by limited distribution have, ironically, been found in new locations as a result of increased inventory work.

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: Texas bluebonnets (Lupinus texensis), Texas snowbells

VISIT: Lost Maples State Natural Area, especially in autumn for fall colors

PLANT LIST »

Cross Timbers

Cross Timbers

The Cross Timbers ecoregion is named for the belts of post oak (Quercus stellata) and blackjack oak (Q. marilandica) woodland that impeded early travelers’ progress across the rolling landscape. The southernmost continuous lobe of North America’s waving sea of tallgrass prairie, this ecoregion is one segment of the great migration “highway” for hundreds of bird species on their commute between winter homes in South and Central America and breeding areas in North America. “Of all these passers-through,” wrote John Graves, “the species that means most to me, even more than geese and cranes, is the upland plover … mainly I know their presence through the mournful yet eager quavering whistles they cast down from the night sky in passing, and it always makes me think what the whistling must have been like when the American plains were virgin and their plover came through in millions.”

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: post oak, Comanche Peak prairie clover (Dalea reverchonii)

VISIT: Lyndon B. Johnson National Grassland

PLANT LIST »

Southern Texas Plains

Southern Texas Plains

Locally called the “Brush Country,” the Southern Texas Plains ecoregion’s gently rolling landscape was once grassy savanna. But after fire suppression and cattle grazing regimes, non-native grasses like invasive buffelgrass (planted to “improve” grazing) took over. Still, this ecoregion is home to a diverse array of subtropical species that reach their northern limits here, including Barbados cherry (Malpighia glabra), a shrub with evergreen leaves and pink, fringed petals. It’s also the heartland for what may be Texas’ most well-known horticultural export, the native shrub cenizo (Leucophyllum frutescens), named for its silvery-gray leaves (“cenizo” means “ashen” in Spanish). When cenizo, also known as Texas barometer bush, blooms after even the lightest of rains, the brush country practically glows in a wash of lilac pink. Outcrops with saline soils sprout unique plants including Johnston’s seaheath (Frankenia johnstonii), a shrub once known in only five locations and listed as an endangered species; it has since been delisted federally thanks to thorough surveying by Texas Parks and Wildlife botanist Gena Janssen, who discovered many more populations now protected by conservation agreements.

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: cenizo, Johnston’s seaheath

VISIT: Falcon State Park

PLANT LIST »

Texas Blackland Prairies

Texas Blackland Prairies

The Texas Blackland Prairies ecoregion runs southwest from the Oklahoma state line to San Antonio, roughly paralleling Interstate 35; another narrower band cuts from the southwest corner of the Piney Woods through the East Central Texas Plains. This ecoregion was once covered with a waving growth of grasses and wildflowers as tall as 8 feet high — not to mention deciduous forest in its bottomland — but less than 1 percent of the area’s original vegetation exists today, making it one of the most endangered ecosystems in North America. Its native plant life and deep, fertile soils were long ago plowed for farm fields and then paved over by development (this ecoregion includes parts of Travis and Bexar counties, home to Austin and San Antonio, respectively). Rainfall ranges from 28 to 40 inches, west to east; the northern part of this ecoregion receives most of its precipitation in spring, making for challenging summer and fall gardening, while the southern part is more subtropical with rainfall distributed evenly throughout the year.

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), white rosinweed (Silphium albiflorum)

VISIT: Heard Natural Science Museum and Wildlife Sanctuary

PLANT LIST »

East Central Texas Plains

East Central Texas Plains

The East Central Texas Plains ecoregion — which forms a broad belt to the east of the Texas Blackland Prairies ecoregion (and is interlaced with it) — is an expression of the effect of substrate on natural communities, especially plants. Unlike the rich soils of the Texas Blackland Prairies, the post oak-dominated savannas of the East Central Texas Plains occupy challenging soils, ranging from those underlain by dense clay layers that restrict available water to deep, loose sands that are porous and nutrient poor. The sandy soils are derived from formations dating back to the Eocene, the time of the oldest known fossils of modern mammals. These soils support nearly a dozen species of endemic plants, including the Texas sandmint (Rhododon ciliatus), a beautiful annual with a spike of lavender flowers, strongly square stems and a lovely fragrance — one of the area’s myriad wildflower species with garden potential. Like many of Texas’ prairie and savanna regions, the East Central Texas Plains ecoregion has suffered from plowing for agriculture, plus re suppression and prairie-dog eradication, allowing woody shrubs and small trees to invade open prairies of waist-high grasses and wildflowers once dotted with mottes of massive old post oak trees.

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: post oak (Quercus stellata), Texas sandmint

VISIT: Gus Engeling Wildlife Management Area

PLANT LIST »

The brackish lowlands of the Texas coast are a far cry from the arid expanses to the far west, further exemplifying Texas’ natural diversity. PHOTO Laurence Parent

Western Gulf Coastal Plain

Western Gulf Coastal Plain

This ecoregion is truly the Texas lowlands, the broad plain along the Gulf Coast that rarely rises more than 150 feet above sea level. A wide band of remnant tallgrass prairie, oak woodlands, saltgrass marshes, estuaries and barrier islands, it receives 23 to 56 inches of rain a year. “This ecoregion’s totemic plants would be [non-native] cotton and sorghum,” jokes botanist Bill Carr, since much of the prairie has been plowed. But he adds, “All the major rivers in Texas go through this ecoregion, which gives it these wonderful ribbons of riparian forest.” Despite extensive alteration by agriculture, oil and gas production, and development, the region’s river bottom forests, estuaries and barrier islands remain critical to migratory birds — both water and land birds — and to the shrimping industry, since estuaries are nurseries for shrimp and also fish.

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: Gulf cordgrass (Spartina spartinae), Texas umbrellawort (Tauschia texana)

VISIT: Brazos Bend State Park

PLANT LIST »

South Central Plains

South Central Plains

The local name “Piney Woods” is apt for this biologically diverse ecoregion where the great southern conifer forests reach their western extent, or as Texas poet Sandra Lynn wrote, “the South stains the edge of the Southwest.” But it’s not all loblolly, shortleaf and longleaf pine (Pinus taeda, P. echinata and P. palustris, respectively): Changes in slope, drainage and substrate create a mosaic of distinct communities. The upland communities, which rest on soils weathered iron red by constant rainfall, feature pine-oak forests on the ridges and, in sandier areas, scattered pines mixed with drought-tolerant cacti and shrubs such as prickly pear (Opuntia spp.) and yuccas. Mid- and lower-slope communities support rich mixes of broad-leafed and coniferous trees with diverse understories, including yaupon (Ilex vomitoria), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana), American holly (Ilex opaca) and horse sugar (Symplocos tinctoria). Wetlands range from pine savannas in the uplands — with carnivorous plants catching insects to supply nitrogen unavailable from acid-rich, swampy soils — to dense palmetto-hardwood flats on poorly drained lowlands and bald cypress-tupelo swamps along sloughs and small lakes. Red-cockaded woodpeckers, Louisiana pine snake and paddlefish are among the endangered or threatened species dependent on this ecoregion.

NOTABLE NATIVE PLANTS: loblolly pine, pitcher-plant (Sarracenia alata)

VISIT: Big Thicket National Preserve

PLANT LIST»

Susan J. Tweit is the author of “Walking Nature Home” and several other books. Learn more and read her work at susanjtweit.com.