The Underworld of Aquatic Arteries

Cave biologists Drew Thompson and Colin Strickland survey a newly discovered cave 60 feet underground. PHOTO Drew Thompson

Most of us cannot begin to comprehend the fascinating world of hidden caves that lies beneath our city streets. It’s a complex network of tubes, streams and underground lakes created by the persistence of water dissolving soluble limestone and then redepositing the calcium carbonate along its path to our aquifer. A strip of the Edwards Plateau limestone stretches through western Travis County, giving us a prime cave-producing region that is referred to as a karst landscape.

Within the last 200 years, most Central Texas cave entrances were obstructed for various reasons. Caves, including ones discovered at the Wildflower Center, have always organically opened and closed repeatedly throughout history. But more recently, as the pioneers moved in, many areas were deforested in an attempt to tame the landscape for livestock and agriculture. As vegetation was removed by overgrazing, and roots stripped that would otherwise hold the soil, erosion deposited sediment within the pores and caves of the karst, obscuring the existence of features. On many occasions, sinkholes were purposely filled with clay to keep water on the surface to create stock ponds. Caves and sinkholes were commonly used as trash dumps without people realizing the impact to local drinking water. Caves have been seen by some as a nuisance or a hazard to mitigate or destroy. The fear that they were habitat for predators, vermin and venomous snakes was a popular reason to fill them in. Other reasons were to dissuade trespassing adventurers; to keep livestock and people from falling in; or to hide karst features to make property more profitable for development. Unidentified caves in Central Texas are covered every day by development. With the ever-increasing rate of urban expansion, developers are rapidly paving over our recharge zone (the area that contributes water to our aquifer).

Colin Strickland and I have been caving for most of our lives. In my late teens, I was lucky enough to have found the local caving club, Underground Texas Grotto, and was able to regularly assist on many different cave research and restoration projects. In 2013, I was hired as a cave specialist for the City of Austin’s Watershed Protection department, and in 2017, I moved over to Austin Wildlands as a cave biologist. Colin, who is a second-generation caver, grew up caving all over the U.S. and in Mexico. His love of the natural world led him to pursue a bachelor of science degree in biology (ecology, evolution and behavior) from The University of Texas at Austin in 2010. He was fortunate to be hired as a cave biologist for the City of Austin in 2017 and plans to continue for the foreseeable future.

City of Austin cave biologists survey a newly discovered cave at the Center PHOTO Drew Thompson

As cave biologists for the Balcones Canyonlands Preserve of the city’s Wildland Conservation Division, it is our job to monitor the overall health of the cave ecosystems and its inhabitants in Travis County’s karst zones. This allows us to ensure there are no negative impacts on the rare and endangered karst invertebrates that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has tasked us with protecting. Additionally, we monitor the groundwater, testing for contaminants. The study of caves and karst is still in its infancy, and we are constantly making new discoveries and re-evaluating misinterpreted information such as the myth that contaminants entering the aquifer are filtered through soil and tiny limestone pores. Caves are more like nature’s storm sewers — the sinkholes act like drains and the caves are like the pipes. There is little to no filtration that occurs. It was once thought that it took years for water to travel underground to Barton Springs from Southwest Austin, but studies have shown water arrives in two to four days.

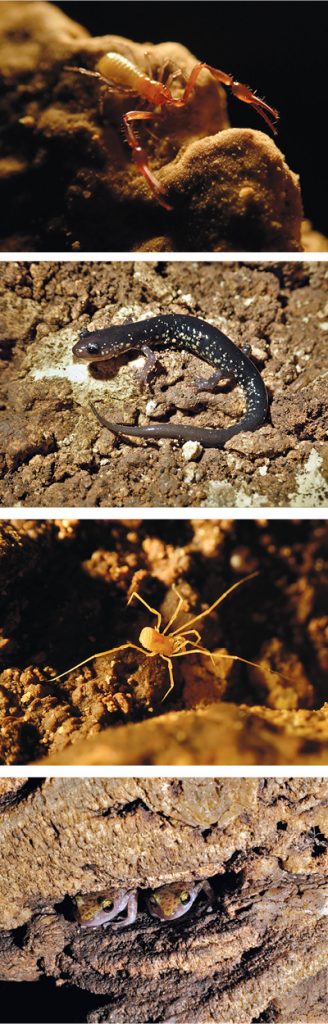

FROM TOP Troglobitic pseudoscorpion (Tartarocreagris attenuata), Western slimy salamander (Plethodon albagula), Endangered bone cave harvestman (Texella reyesi), Cliff chirping frogs (Eleutherodactylus marnockii) PHOTOS Colin Strickland

Cave studies are important because they are the aquatic arteries of the Hill Country, rapidly taking rain from the uplands and dispersing the water through the subsurface to fill our aquifers and discharge from springs. If that water can’t make its way into a cave, it will flow above ground, adding to the amount of runoff from our creeks and rivers and increasing flooding downstream. Also, the Balcones Fault Zone has very diverse cave fauna. Due to downcutting (vertical erosion) from rivers and streams, as well as displacement on faults, there are lots of isolated “islands” of cavernous limestone. This caused several groups of troglobites (organisms that live solely underground) to evolve into closely related species over short distances. Travis County has many endemic troglobitic karst invertebrates with very small ranges. Driving across Austin, you’re likely to pass over the ranges of multiple species of eyeless cave beetles, pseudoscorpions and spiders.

The subterranean environment is very low in nutrients due to the complete lack of sunlight and subsequent absence of plant life. Nutrients only enter cave ecosystems by falling or washing into entrances or being brought in by trogloxenes (cave guests that typically live in the cave during the day and forage outside of the cave at night). A cave, no matter how large, will have little biological activity without an input of nutrients from the surface. On multiple occasions, after removing soil and rock from filled caves with no opening to the surface, we found the rooms below were lifeless. Our biological monitoring shows that species diversity and abundance increase after the entrance is restored — colonized by cave crickets, cliff chirping frogs, western slimy salamanders and sometimes bats. These organisms, their eggs and their guano, combined with an influx of organic debris, provide nutrients to the cave ecosystem. Fungus and bacteria grow and feed tiny cave springtails which become prey for troglobitic species.

Caves are a wonderful resource that we all need to try to understand and protect. One way to increase awareness of this resource is by restoring caves for use as underground classrooms. At the the Wildflower Center, there are two caves where tours led by multiple city departments, thousands of local children are educated each year about the importance of karst. Cave excavations have been active locally since the 1950s. Without the local cavers locating and restoring them, we would have only a very small fraction of the caves that we have currently, since filled caves are easily overlooked and covered by development. Caving is often misrepresented as an extreme sport, categorized with rock climbing or associated with white water rafting — as if the cave is a thing to conquer. The passion of caving is the unquenchable curiosity about the underground. True cavers are scientific explorers who are constantly in pursuit of new insights into this rarely seen world.

If you’re interested in learning how to help protect caves, visit austintexas.gov/department/wildlands-conservation.

If you’re interested in going caving, visit Travis County’s local caving club, Underground Texas Grotto, at utgrotto.org.