Protecting Ash Trees

When Center conservationist Minnette Marr hiked an hour into Hudson Woods Wildlife Refuge back in 2009, two challenges lay ahead. Would the seed casings she collected from a 30-foot-tall ash tree between cloudbursts be too wet to preserve for future use, and would any baby alligators that had separated from a protective mother cross her path?

Like many ash species, the green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) that Marr targeted is a water-lover found mostly along flood plains and river banks, such as Texas’ coastal wetlands that alligators frequent. The future of this green ash is in question along with that of 340 million-plus other ash statewide. They are threatened by a beetle responsible for the deaths of millions of ash throughout the East and Midwest.

LEFT Texas ash in residental yard (Fraxinus texensis). PHOTO Benny Simpson CENTER Green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) dropping it’s leaves in the fall. PHOTO Sally and Andy Wasowski RIGHT Mexican ash (Fraxinus berlandieriana) in Kerrville Texas. PHOTO by Norman Flaigg

Luckily for Marr, a coonhound wandering the trailhead south of Houston where she started her trek served as a sentinel along the refuge’s Oyster Creek, where gators can reach 8 feet in length. The rain and lightning that October day let up sporadically, too, providing time to knock the tree’s oar-shaped seed casings onto a tarp below.

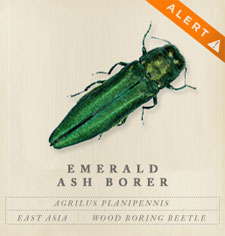

The 2,500 seeds that fell are now safely stored at the Wildflower Center for future conservation efforts along with seeds from Texas ash (Fraxinus texensis) and Mexican ash (Fraxinus berlandieriana). Some Texas ash seeds are also with University of Wisconsin – Madison researchers seeking an inexpensive, natural deterrent to Emerald Ash Borer, the beetle with nine Texas species of native ash in its crosshairs. And Marr is among a growing army of naturalists and laypeople striving to keep the wood-boring insect from settling in the Lone Star State.

“In urban areas, ash trees provide shade and habitat for birds and insects very quickly because of their fast growth rates,” Marr says. “And in riparian areas like along the Colorado River, green ash is used by birds and butterflies and insects – all kinds of wildlife – for food and shelter.”

You can help stop the spread of Emerald Ash Borer and the effects to native trees

You can help stop the spread of Emerald Ash Borer and the effects to native trees

To learn to identify Emerald Ash Borer, signs of ash infestation and other facts, visit: emeraldashborer.info.

See the 12 worst invasive pests and plants that might reach Texas

To organize and host a Sentinel Pest Network workshop in Texas to help identify the “dirty dozen” listed above, contact Jessica Strickland at [email protected] or 512-232-0107.

Learn what other pests make moving firewood around a bad idea.

Learn about an Emerald Ash Borer trap project in Texas

When a decades-old ash dies, she adds, nearby plants and waterways lose out on shade, as well as space being opened up for invasive exotic plants that compete with native ones for resources.

A $74,000 grant from the U. S. Department of Agriculture allows the Wildflower Center to teach Texans how to track down evidence of the metallic green beetle and 11 other invasive pests and plants of concern. Some citizen scientists previously trained by the Center and attendees of the first of these free Sentinel Pest Network Workshops have also joined a multi-agency project to hang more than 1,500 sticky traps on ash trees in the most susceptible Texas counties. Traps in the project are overseen by the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. They will be checked in June and August for any adult Emerald Ash Borer that might have reached the state.

In addition, committed Wildflower Center volunteers Gerin and Dell Hood donated $15,700 to fund future seed collections of white ash and green ash in East Texas so that trees can be reintroduced if they are harmed. “We’re real believers in native plants,” says Gerin Hood, who like her husband is a master naturalist and a volunteer at the Center since 1994. “If it is native, it’s part of the state’s natural habitat and it’s not trash to us.”

The stakes are high because Adult Emerald Ash Borers can fly up to half a mile to reach a new host. The beetle is a recent introduction – suspected to have hitched a ride to North America within ash wood used as packing material in Asia via Michigan, where it was detected in 2002. It has since wreaked havoc in 15 states and in Canada.

Infested trees, which die when the insect’s larvae eat a nutrient-rich layer beneath their bark, have sometimes been found hundreds of miles from previous infestations. The list of possible vectors includes people unknowingly moving ash firewood to new locations.

To help prevent the insect’s spread, the Wildflower Center’s invasive species manager Jessica Strickland will lead nine more Sentinel Pest Workshops this year where volunteers practice identifying invasive pests and the vegetative damage caused by Emerald Ash Borer, the Gypsy Moth, an African snail and other invasive pests and plants that haven’t reached Texas yet. That ‘dirty dozen’ list is also on the radar of the Invaders of Texas citizen science program Strickland directs, which has 1,436 volunteers.

According to Strickland, “When people attend these workshops, they become incredible advocates about invasives and help other Texans become engaged in keeping our landscapes healthy.”

Meanwhile, Marr followed up on her Hudson Woods collection supported by the Houston Endowment with collections of Mexican and Texas ash in the Edwards Plateau assisted by landowners Billy Hutson and Don and Ann Connell. Those collections are a tiny portion of what she will need to complete soon from ash that are in historically undeveloped landscapes.

Marr says, “With the ash conservation project, we will collect seeds from 50 trees in each ecoregion where they are found and store the seeds from each tree separately.”

For a species like green ash that occurs in four ecoregions, that means collecting thousands of seed pods from 200 trees with the help of volunteers the Wildflower Center hopes will join in on the effort.

But Marr remains undaunted, noting that it’s the most important work she is doing. “If one of those trees shows some resistance to the Emerald Ash Borer that the others don’t, researchers will be able to walk back to that tree and collect additional seeds for reintroduction projects.

“We’re sadly aware that we’re going to lose ash trees in Texas,” she adds. “The threat is that imminent.”