A Place and a Promise

The wildflowers carpeting the Texas countryside each spring attract thousands of visitors eager to see denim-blue fields of bluebonnets (Lupinus texensis), swaths of yellow and red flame acanthus (Anisacanthus quadrifidus), disks of sunset-hued firewheel (Gaillardia pulchella) and more. Attractive ambassadors indeed! But the Center has never been solely about pretty flowers. “Mrs. Johnson said that the Wildflower Center is both a place and a promise,” says Executive Director Lee Clippard. “We are a place where people can connect with nature and native plants — where we are actively displaying and conserving native plants. The promise is being made to future generations, and that’s through our education and the science and research that we can pass along.”

This year, the Wildflower Center celebrates its 40th anniversary. Over the past four decades of pursuing the mission to inspire the conservation of native plants, the Center has grown from a private nonprofit research organization mailing out one-page flyers, to a public botanical garden visited by almost a quarter million people in 2021. It’s become an educational hub for homeowners, citizen scientists and public landowners, and a publisher of a comprehensive online database of North American native plants. The Center has also become a seed bank of Texas plants, a developer of Habiturf® (a native turf grass mix) — a part of the University of Texas — and a participant in important ecological research. These achievements are due to the hard work of many dedicated and passionately invested people — from the Center’s namesake founder, executive directors and board members, to the staff, volunteers, donors and members. The humble Wildflower Center has opened a lot of doors and minds — and continues to do so today.

Growing the Wildflower Center

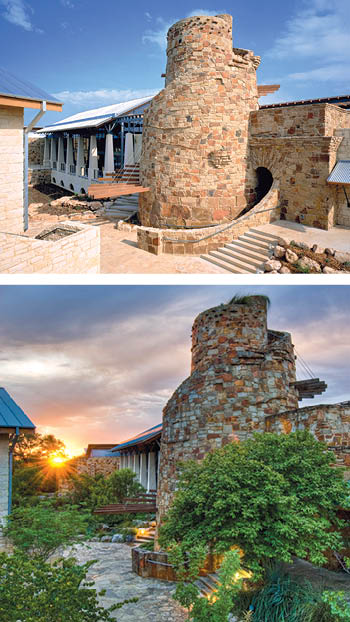

TOP A 10,000-gallon stone cistern doubles as an observation tower offering dramatic views of the Center, prior to the grand opening PHOTO Timothy Hursley BOTTOM The golden sunrise shining light on the Observation Tower, gardens and the Great Hall. PHOTO Wildflower Center

In December of 1982, on Lady Bird Johnson’s 70th birthday, she donated 60 acres of land in East Austin and $125,000 to establish — with co-founder Helen Hayes — the National Wildflower Research Center. “Most people think of 70 as a time for retirement,” says Luci Baines Johnson, “not as a time to begin a brand-new national project. But Mother wasn’t most people.” At the time, the native-plant movement was in its infancy and much about native plant botany remained unstudied. “There was a lot we didn’t know about seed propagation [or] plant propagation for our native plants,” says Clippard. “Did they need to freeze? Did they need to be planted at certain times of the year? Lots of basic information like that. There was a huge effort to not only gain that knowledge through research and practice but then share that with the rest of the world.

The Center operated purely as a private research facility in the early years, with wildflower plots for horticultural research. But even though it lacked public gardens, visitors showed up anyway. “People really wanted to visit,” says Clippard. “School groups wanted to come through; tourists would arrive there.” Leadership quickly recognized that the Center should expand to become a public facility.

In 1995, the Center relocated to a 42-acre site in Southwest Austin, nine miles from downtown, in a scenic transition zone between the limestone escarpments of the Edwards Plateau and the deep gumbo soils of the Blackland Prairie. The new location offered visitors a distinctly Central Texas landscape to explore — five acres of native-plant gardens and natural areas designed by J. Robert Anderson (FASLA and principal), Eleanor McKinney (EMLA) and Darrel Morrison (FASLA), along with a building complex designed by Overland Partners. Clippard says that the Center welcomed about 40,000 people through the garden gates that first year. This year (2022), it’s expecting more than 230,000.

Children observing aquatic wildlife and native Texas plants in the Wetland Pond at the Center’s entrance. PHOTO Thomas McConnell

Not only do the gardens connect to the natural landscape, but to the award-winning architecture of the Center’s buildings, as well. The structures reflect three main influences in Texas vernacular architecture: Spanish colonial (which shows up in rusty sandstone arches in walls, aqueducts and the observation tower), German settler (as seen in solid limestone-block construction) and Texas rancher (evoked with corrugated steel siding and silos). Landscape architect J. Robert Anderson worked closely with the structural architects to blend buildings with the gardens and meadows using local stone and experienced local masons. “We brought in limestone and sandstone in walls that we built, and we harvested and reused boulders found on-site,” says Anderson. “There are some tall walls on the north side of the Great Hall that hold up the terrace. We found accomplished rock workers to tie the building to the land with those walls. It’s almost a transition from the geology of the land itself up to the building. One of the best compliments we got was, ‘You can’t tell where the landscape stops and where the architecture starts.’”

The buildings provided space to expand the Center’s educational offerings through new classrooms, a 240-seat auditorium and the Little House for children. Planted exclusively with Texas plants, the new gardens showed visitors that natives can be used the same way as traditional garden plants, but with less water and without the chemicals often needed to keep fussy exotics thriving in the hot and humid, drought-to-flood Central Texas climate. “The Wildflower Center made people appreciate native plants for their beauty, and not just because it’s the thing to do or a landscape ordinance requires more native plants,” says Anderson, “And that appreciation of beauty — the inherent nature of why we love bluebonnets — in many types of native plants loosens up our landscape palette to make nontypical front yards look interesting and cool. It’s a huge achievement that the Wildflower Center inspired people to do.”

By 2002, the Center’s original 42 acres had expanded to 284 acres, securing a buffer zone of natural landscape around its core gardens and opening space for the Mollie Steves Zachry Texas Arboretum and the Luci and Ian Family Garden. The additional acreage also allowed room for prescribed burn research and its impact on native plant diversity. “When we added the rest of the land,” says Clippard, “it was transformative, and it protected it for future generations. We’re stewarding this important and sensitive piece of land, and it made our southern border contiguous with other green spaces — water-protection land and parkland — that will never be developed.”

Forty Years of Native Plant Advocacy and Research

The Wildflower Center exists not only as a physical place but also as an online resource. Since those early years of stuffing one-page flyers into envelopes, the Center has developed the Native Plants of North America online database that contains information about every native plant in North America north of Mexico — about 25,200 plants. “We don’t have Mexico in there yet,” says Clippard, “but that is a goal for us.” About 2.4 million people currently use the database every year. “Everyone uses it,” Clippard says. “It’s used by citizens, gardeners, by landscape architects, and for research and science. It’s one of our most popular tools, and it really goes back to our core mission, which is sharing information about native plants.”

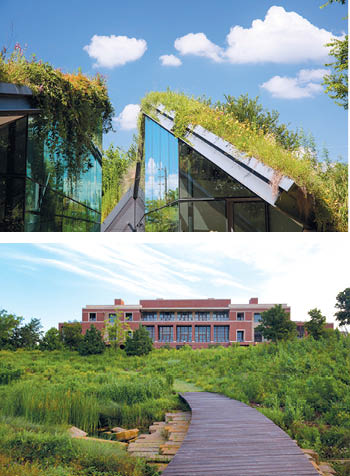

TOP A SkySystem™ greenroof at the Edgeland House in Austin designed by Wildflower Center environmental designers. PHOTO Paul Bardagjy BOTTOM Center experts led design on the LEED platinum certified George W. Bush Presidential Center in Dallas. PHOTO John W. Clark

The Wildflower Center also led the development of the Sustainable SITES Initiative (SITES®) — a green program and rating system used by landscape architects, engineers, developers, ecologists and others in land development and management. “That project has had international impact through all of the projects that are now being SITES-certified,” says Clippard. Our team has worked with architects, landscape architects, engineers, resource managers, conservation professionals and multidisciplinary design teams on projects at multiple scales. We have worked on high-impact projects for public and private clients, including national and regional parks, corporate headquarters, urban developments, institutional campuses, river and prairie restoration, state highways and botanic gardens, that includes things like the George W. Bush Presidential Center in Dallas and the Waterloo Greenway project in Austin, all to help developments use native plants appropriately. Those projects cumulatively impacted almost 90,000 acres in Texas. And hopefully through that, we’ve been able to demonstrate how beautiful native plants can be and how we can support native environments.”

Research has been a constant throughout the Wildflower Center’s 40 years. The Center’s longest-running research project — spanning the past 22 years — has been an examinination of the impact of prescribed fire and grazing on oak-savanna landscapes. “We’re finally seeing some trends in the data,” says Clippard. “And we’re starting to overlay new research on top of that — looking at pollinators and bird diversity and soil. We’ve hired a restoration ecologist to lead our Science and Conservation program. I think that’s going to bring a unique perspective to our research by linking plants to their wildlife and pollinators.”

The Center’s research arm was also instrumental in making green roofs feasible in hot climates. Green roofs are important tools for making cities resilient to climate change by capturing rainfall and reducing runoff, lowering a building’s heat load and need for air conditioning and removing carbon and other pollutants from the air. They also provide essential habitat for birds and pollinators in our increasingly urban world. But even as green roofs were taking off elsewhere, they faltered in hot climates, where traditional rooftop plants struggle to survive in harsh conditions. In response, Wildflower Center researchers developed a growing medium designed for green roofs in semi-arid climates, allowing them to succeed in Texas and beyond.

In 2006, the Wildflower Center joined The University of Texas at Austin. Luci Baines Johnson says that union was a comfort to her mother. “When Mother started the Wildflower Center,” recalls Johnson, “she realized there was a whole lot more life in the rearview mirror than that which lay ahead. Like every mother, she wanted to make sure her child would thrive independently on its own when she was no longer here. Mother believed that The University of Texas was going to be here till Gabriel blew his horn, and she felt like, if her Wildflower Center could be a part of the University of Texas family, it could help young students want to pursue their life’s work in the environment.” Clippard also sees the value of being part of the university. “It provides an amazing opportunity for us to be part of world-class research happening across campus,” he says. “There are faculty and graduate students studying biodiversity and climate change, and that’s our wheelhouse. We’re able to provide a resource for all of that research and education. It gives us an opportunity to expand our impact.”

Science and Conservation research team identifying plants during a veggie survey in 2021. PHOTO Sean Griffin

Focusing on the Future

When the Wildflower Center was established, Austin’s population was 358,950. Today it’s over 1 million and growing rapidly. With so many people pouring into the Austin area, and with housing and commercial development gobbling up open land, the Wildflower Center has become an urban refuge sooner than perhaps anyone could have imagined 40 years ago.

Lady Bird Johnson, who was only five when she lost her mother, found consolation outdoors in sunny meadows and in the cool shadows of trees. As an adult, she never forgot the healing power of nature. “Mother felt that nature could do so much for humankind’s ills,” says Luci Baines Johnson. “It could lift your spirit. It could make where you live a healthier, happier place.” That sense of refuge and healing is more important than ever to the Center’s mission. “As Austin grows and we become this giant metropolitan area,” says Clippard, “the role the Center can play in human health is becoming more and more central to our purpose.” Landscape architect Anderson agrees. “There’s a health issue that’s provided by a garden,” he says. “It offers a sense of relaxation, getting away from the world, not being next to paving. I think health is an underappreciated part of open space and gardens. And man, do we need something to de-stress our lives right now, after two years of COVID.”

As Austin and the Wildflower Center have grown, more and more people have been able to visit and learn about native plants. Clippard hopes even out-of-state visitors “gain an appreciation for the native plants in their own state, and start thinking about how they can support pollinators and wildlife.” Of course, more people visiting means more cars in the parking lot and more foot traffic in the buildings and gardens. “One of our biggest challenges ahead is figuring out how to accommodate the growth in our community and serving the growing community best,” says Clippard. “The potential for us to impact people is great, but we need to do that in a way that’s protective of the environment and equitable for everyone.” Plans are currently underway to redesign the garden’s main entrance to allow easier public access to the gift shop, café and restrooms. “We want to pull those facilities out to the front,” says Clippard, “and make them more accessible as a resource for the surrounding community.”

Mrs. Johnson standing in a field of wildflowers near Stonewall, Texas in April 1985. PHOTO Dennis Fagan

A Gift of Hope

Despite the enormous challenges of our time — climate change, habitat loss and species extinction, to name a few — the Wildflower Center is positioned to be a responding leader. After all, as Lady Bird Johnson recognized 40 years ago, native plants give us much that we take for granted: Species diversity and a distinct sense of place that feels like home; habitat for wild creatures that evolved alongside those plants; healthier landscapes that don’t require chemical interventions to thrive; and gardens better able to cope with extreme weather events. With the amount of global change happening, native plants need our help as much as we need theirs. “People can take action to save and foster native plants,” says Clippard. “There’s so much we can do to improve our environment, and the Wildflower Center will continue to play a pivotal role in inspiring people to do so.”

Reflecting on today’s challenges, Luci Baines Johnson recalls her mother’s oft-quoted words: “Where flowers bloom, so does hope.” “There’s lots of discord in the world today,” says Johnson. “But the Wildflower Center is not a place where that blooms. Hope for tomorrow, that was Lady Bird Johnson’s work. The environment is where we all meet, as Mother said. It’s something we can protect and celebrate. Where flowers bloom, so does hope… and what greater gift is there than hope?”

Austin writer and photographer Pam Penick is always on the prowl for interesting gardens to share on her website, Digging (penick.net), where for 16 years she’s been publishing “all the gardening goodness she can dig up.”