Coming Home

When I was little, I lived on a school bus that my dad modified into a two-story home. We were nine miles up a gravel road from the Pacific Ocean on the Oregon Coast. We were forty-five minutes away from just about anything else. There aren’t a lot of photos of our family from those days, but in most of them I’m shaggy-headed, covered in mud and at least partially naked.

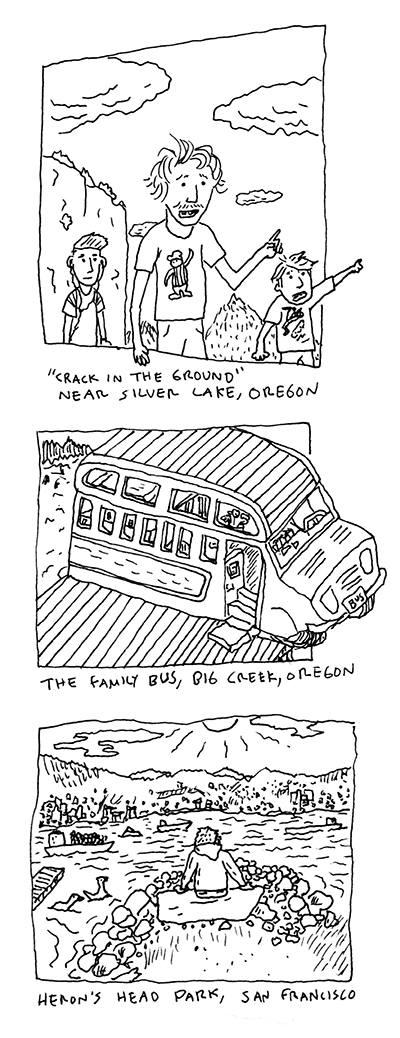

My parents weren’t hippies, exactly — my dad’s a socialist carpenter from England and my mom is a new-agey barber from Minnesota — but they did love the wilderness, and because wilderness was still pretty cheap in those days, they bought some. By all accounts, I loved it too. I picked berries, screamed my head off and swam in the summertime. Most summers, my dad would drive me and my brother out to the vast deserts of Eastern Oregon in his old Ford van. Often, dad would pull out a map and let my brother and I pick the destination. We’d wind up at natural tourist attractions in desperate need of new marketing teams: places with names like “Hole in the Ground” and “Crack in the Ground.”

Most of my friends had a different relationship to nature than we did: They’d go to the lake to fish or go into the forest to hunt. My family went places just to be there, and we didn’t have to go far off the beaten path to be the only humans in sight. Oregon, in the late ’80s and early ’90s, still felt like a secret.

But when you’re surrounded by beauty, eventually you get spoiled. Somewhere in my teens, it’s like I stopped seeing nature altogether. When I went off to college at the University of Oregon in Eugene, I was fascinated by live music and coffee shops and friends with difficult relationship problems to solve. Moving to Portland after college provided me with dive bars and rock clubs every night of the week. Nature couldn’t really compete. I’d still check in with it a few times a year — usually by sitting on the beach in the middle of the night, waiting for something spiritual to wash over me that never did.

I thought I’d lost that sensitivity to nature forever. Then, four years ago, I moved to San Francisco for a job. I slept in a small room that didn’t feel like home. Outside of work, I had no engagements, no responsibilities. So I’d spend full days just wandering the city with no destination in mind. And for all its problems, San Francisco was a great place to rediscover nature: It had weird little overgrown parks that no one seemed to visit, patches of alien-looking succulents that couldn’t grow back home. The fog would roll in and the whole city would feel strange and new. There may have been other humans in sight, but I still felt alone. I read about the plovers and avocets I’d watch in the wetlands at Heron’s Head Park and the non-native eucalyptus trees that have proliferated around the city. I read about the slow geological process that built up the serpentine hills in this strange, magic place.

When the job ended and I came home to Oregon, I got to see it with new eyes for a while. And even now, as its natural beauty fades gently back into the realm of the known, I work on it. Long relationships require some work. I try to explore more, read more about the places I visit and breathe a little deeper. I try every day to see this place the way a stranger would see it. And sometimes I still sit on the beach, waiting for some profound appreciation. Usually I just feel like I’m home, and I’m grateful for that.

Casey Jarman is the author of “Death: An Oral History” and writes about music (and basketball) for a variety of publications, including Willamette Week, Nylon, Portland Monthly and Next American City. He is illustrations editor for the Believer and illustrated this story.