Wild About Monarchs

A monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) drinks nectar from a swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata). PHOTO Val Bugh

JUST OUTSIDE OF LEXINGTON, TEXAS, a stretch of roadside off of Highway 77 boasts a simple black sign labeled “Tanglewood Prairie” on a barbed-wire fence. Behind the fencing rests a sandy field of healthy Post Oak savanna that Minnette Marr and Tara LeBlanc headed into on a recent muggy morning in search of milkweeds.

To enter the prairie thick with little bluestem grasses meant walking through patches of reddish-tinged poison ivy and its look-alike neighbor, pepper vine. The dark green, prickle-covered stems of Southern dewberry were also prevalent at Tanglewood, and can leave someone who brushes into them itching for weeks. “I’d rather wrangle with poison ivy any day over dewberry,” Marr noted.

Despite the challenges, the opportunity to help native plants survive buoyed the plant conservationists from the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. “There’s no place I’d rather be on a workday morning,” noted LeBlanc.

Their scouting excursion at the 31-acre prairie is part of a monarch project funded by a grant the center received from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. As a participant in the Service’s Texas Native Pollinator Initiative, the center received $50,000 to help ensure that monarchs traveling through Texas have native milkweed.

Why worry about milkweed species when ample rains this year have meant the plants are likely plentiful in many Texas counties? Because drought is likely to return in future migratory seasons. And much of the land in North Central Texas that the center is focusing on has been ploughed under or built up. In addition to fragmented habitat along the I-35 corridor, monarchs that may migrate a thousand miles can face weather conditions such as deadly cold snaps, and the stress of being susceptible to diseases and parasites.

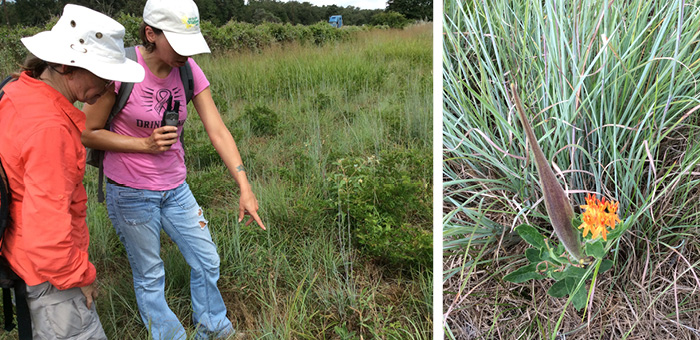

Wildflower Center Plant Conservationists Minnette Marr (left) and Tara LeBlanc discuss their first sighting of a pineland milkweed (Asclepias obovata) amidst native grasses at Tanglewood Prairie. Photo by: Barbra Rodriguez. (right) A butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa) with a developing seed pod and blooms at Tanglewood. The plant conservationists received permission to collect milkweed pods there by land owner Texas Land Conservancy and the Native Prairies Association of Texas, which holds a conservation easement. PHOTO Barbra Rodriguez

Citizens who want to help monarchs can struggle, too. Milkweeds are the only plants monarch larvae can develop on, but native milkweeds are not easy to come by. Some species are simply tough to propagate. “There are plenty of landowners, schools, churches, public libraries and others who want to help out,” Marr said. “But the commercially available milkweed seed is too expensive or unavailable.”

The Wildflower Center has a three-pronged strategy to make more milkweed available for monarchs that leave Mexico and lay their eggs in Texas in the spring and summer, and for adults headed back south this time of year to overwinter in Mexico. With the grant funding, center staff are collecting seeds from native milkweed plants in North Central Texas counties and sharing the bounty; studying ways to improve large-scale propagation of milkweed species; and offering future community workshops to Texans interested in propagating local milkweed.

“Getting involved in this is a very logical progression for us,” says Karen H. Clary, Ph.D., the Center’s program manager for plant conservation. “We understand very deeply the relationship between plants and pollinators.”

In the case of milkweed, the relationship stems from a need monarch caterpillars have to dine on milkweed. By doing so, the slow-moving larvae ingest protective plant chemicals called cardiac glycosides that are toxic to birds and other predators. Resulting adult monarchs also contain the toxic chemicals, and most birds avoid them.

Susan Prosperie, Center propagation specialist, shows the dense roots on a Zizotes milkweed (Asclepias oenotheroides). Prosperie is helping oversee thousands of milkweed plants being grown from seed at the center with the Fish and Wildlife Service funds. Photo by: Barbra Rodriguez. (right) Butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa) prepping to bloom at the center’s shaded Tree Nursery. PHOTO Barbra Rodriguez

Schoolyard Greening

As the center’s plant conservationists collect milkweed pods from wild plants, those grown from previous collections are already finding homes. Five hundred milkweeds will be shared with Austin area schools this month as part of an outreach component of the grant that includes the National Wildlife Federation. Marya Fowler, the federation’s senior education manager, joined center and city staff in September for an initial workshop at the center to educate teachers from local schools about the monarchs and the 50 plants each teacher will soon receive.

Closeup of a showy milkweed (Ascelpias speciosa), among the Texas native species the center will share soon for gardens at elementary and middle schools in the Austin Independent School District. PHOTO Terry GlaseThe plants will include antelope horns (A. asperula) grown from seeds collected by the center on site, Zizotes milkweed (A. oenotheroides) from seeds that were among some of the 6 million collected during the center’s participation in the Millennium Seed Bank project, and seeds from four other species such as showy milkweed (A. speciosa).

Closeup of a showy milkweed (Ascelpias speciosa), among the Texas native species the center will share soon for gardens at elementary and middle schools in the Austin Independent School District. PHOTO Terry GlaseThe plants will include antelope horns (A. asperula) grown from seeds collected by the center on site, Zizotes milkweed (A. oenotheroides) from seeds that were among some of the 6 million collected during the center’s participation in the Millennium Seed Bank project, and seeds from four other species such as showy milkweed (A. speciosa).

Fowler will help the teachers at five middle and five elementary schools in educating their classes about how to incorporate their new green charges into school gardens. An additional 10 schools in the Austin Independent School District will be tapped to receive milkweed plants next spring.

“The monarch is a tangible species that is in trouble and that children can help,” said Fowler. “Children can see them in their own schoolyards and backyards and develop important stewardship skills when they create habitat and care for monarchs. And when they realize they can make a difference for the monarch, hope becomes a reality.”

These school gardens won’t simply provide pollination stops and shelter for monarchs. Native Texas species of milkweed (which are likeliest to thrive since they are adapted to local environments) also support wildlife such as bees, beetles and hummingbirds. “If we can keep as many native milkweeds available throughout the growing season as possible,” Minnette Marr said, “monarchs will have them while migrating and other pollinators will benefit to boot.”

Finding Milkweed

As the conservationists surveyed plants hidden within the bluestem grasses stretching skyward at Tanglewood Prairie, they hit the jackpot and found several milkweed species. A strip of prairie as wide as a two-lane road had been receiving intermittent mowing, keeping Eastern red cedar and other saplings from growing up and shading the ground. In that sunny strip they unearthed a solitary pineland milkweed (Asclepias obovata) in bloom, as well as some blooming butterflyweed (A. tuberosa). Moreover, they found Zizotes (A. oenotheroides) growing closer to the highway, some with seed pods ready to collect. While some milkweed species require specific soil and moisture conditions, this un-fussy species could work well for many settings, Marr noted.

Sharing the Plunder

The center has grown seeds collected by staff, purchased from Native American Seed or from previous collections for the Millennium Seed Bank. Nursery Manager Sean Watson and Propagation Specialist Susan Prosperie oversee the care of 3,000 milkweed plants already, or about half of what they hope to provide through outreach efforts before next summer.

To shore up future milkweed supplies, they will conduct studies this fall and next spring to compare how well seeds respond when exposed to different germination conditions for different time lengths. “The challenge is to get milkweed to a size where you can transplant them and get them to a mature size for sharing,” Watson said. “It’s not unusual for milkweed to die early on from damping off or rot from overwatering.”

A water-loving plant like swamp milkweed (A. incarnata) survives easier. But that means it is readily available commercially. Watson and Prosperie will focus on trickier species that include antelope horns (A. asperula), zizotes (A. oenotheroides), green milkweed (A. viridis) and other challenging species. They will also test environmentally friendly approaches to reducing the aphids that tend to plague milkweeds and other survival strategies. “If we can establish a good protocol on how to propagate and cultivate milkweeds, that can make a huge difference in how many people grow them,” Watson said.

The germination protocols would be shared with commercial growers and people who sign up for online workshops beginning October offered by Clary and the center’s Professional Development Coordinator, Jonathan Garner. The webinars – provided free through the grant – will help Texans learn to identify, collect seed and propagate milkweed in their own region in the hopes that monarch sightings continue statewide for a long time.

Clary said, “The impact of this outreach effort could be huge in terms of helping ensure that future generations see monarchs flitting through their landscapes. For many, it’s a treat and an anticipated part of the change in seasons in Texas.”