With Botany and Two Burros

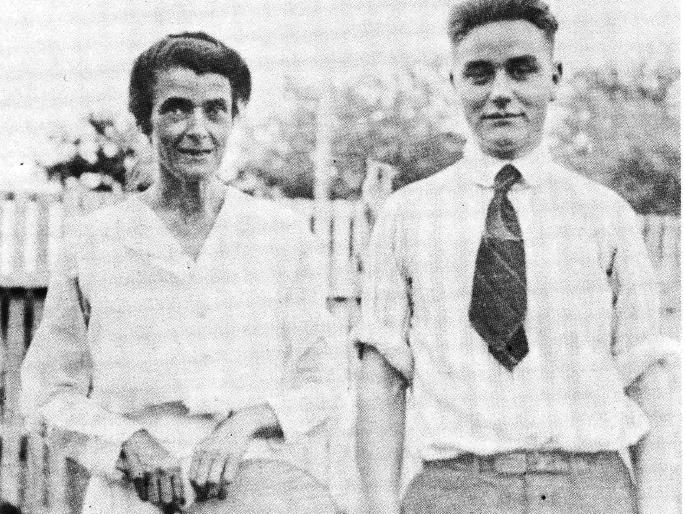

Young in West Texas with her $10 buggy and two slow, difficult donkeys. PHOTO courtesy of the Texas State Historical Association/Southwestern Historical Quarterly

Pioneer plant collector Dr. Mary Sophie Young is best known as the botanist who ventured out to the wilds of West Texas to systematically study and collect native plants in the early 1900s. And collect she did — in a skirt.

Young mounted four trips to the mountains, deserts and rivers of the Trans-Pecos, collecting a whopping 1,700 plant specimens with the help of an assistant, an open buggy and two burros. Many of the plants were previously unknown from the Trans-Pecos and some of them later described as new species.

Even by today’s standards, the pace of field work required to make such collections in this rugged country is monumental. Equally amazing is Young’s logistical prowess and sheer force of will to plan and execute these expeditions. She kept detailed field journals of her collections and travels, and it is through them that we know about her work. This year we commemorate the 100th anniversary of her passing.

A Botanist’s Botanist

In 1912, Young — who earned a doctorate in botany from the University of Chicago — became the first curator of the nascent University of Texas at Austin herbarium. During her tenure (through 1919), she grew the herbarium from 2,500 specimens to 16,000, up to 10,000 of them from her own collections. Today the herbarium is the largest in the Southwest, housing over 1 million specimens, and boasts the most holdings of Texas plants in the world.

When Young wasn’t working at the herbarium or as a botany instructor, she explored the plant life of the Austin area. Though the Ohio native’s life was cut short by cancer, to which she unexpectedly succumbed at the age of 46, her dear friend and fellow botanist Dr. B.C. Tharp published the manuscript for her ongoing project, “The Seed Plants, Ferns and Fern Allies of the Austin Region” (about 720 taxa) the following year. We would know much less about Young if Tharp hadn’t taken it upon himself to share her work.

In the preface, he writes: “It represents six years of as intensive collection as was possible for an enthusiastic, energetic, and thoroughly capable person who was doing at the same time a full share of teaching work. With exceptional skill Dr. Young has in it not only blazed a trail; she has actually builded [sic] a highway.”

Into the Wild

It is through her personal journals — also published posthumously with Tharp’s help — that we learn of her adventures out west. On her first trip in 1914, Young was accompanied by Carey Tharp, the younger brother of B. C. In the early 1900s, the Trans-Pecos was hard to reach. They traveled by rail from Katy to Marfa, then took the unmaintained, uncharted wagon roads connecting the few towns and ranches that existed.

In Marfa, they bought a used horse buggy for $10 and two obstinate, delinquent burros they named Nebuchadnezzar and Balaam. She wrote of the former, “If our Lord rode as lazy a beast as this one, the triumphant entry into Jerusalem must have taken a long time.”

Young and her collecting assistant, UT student Carey Tharp. PHOTO courtesy of the Texas State Historical Association/Southwestern Historical Quarterly

Over the next six weeks, while mastering the art of burro and buggy livery, Young and Tharp worked their way northwest to the Davis Mountains, where they collected in foothills, canyons and mountains, including Mount Livermore. Of Tharp’s willingness to wade up to his hips in a stream (to deal with some donkey and wagon chaos), she wrote: “My respect for 17-year-old boys brought up on farms grew considerably.”

The second leg of their trip took them west to Valentine, through the pass at Capote Peak to the Rio Grande, where they collected plants in the vicinity of the Chinati Hot Springs. Young noted with humor that the burrows weren’t the best fit for a buggy made for horses, but it was good enough and served them the whole season. It carried their collecting supplies, camping equipment and basic food rations: bacon, beans, cornmeal, sugar, coffee, rice and butter. Windmill tanks and mountain springs supplied fresh water. They supplemented their diet with what game they shot along the way, largely jack rabbits and cottontails, and once foraged peaches from an orchard.

At the end of the season, the buggy and burros were traded to a photographer from El Paso who met them in Ruidosa. He had no money, so the rig was traded for his shotgun, cartridge belt and all the pictures Young wanted.

The youngest of eight children and the only girl, Young’s fearlessness is clear in her writings; she relished the challenge and adventure that fieldwork brought.

A Lasting Legacy

The best way to get to know Young is through her journals. Her own words reveal someone independent, bold, funny, adventurous, a devoted scientist, resolute and, yes, a woman totally alone in her pursuit. Hers is a timeless story of grit, determination and scientific achievement against the odds.

B.C. Tharp described Young as having “a healthy coat of tan that gave unmistakable evidence of much outdoor life.” Though seemingly less obvious, he also said even a casual observer would note her “preoccupied air.”

It’s this attribute that kindred botanists can relate to most. Once you recognize that you are obsessed with the plant world and all it can reveal about the order of life on Earth, you become preoccupied in a most gratifying way.

With Young’s innate curiosity as our guide, we follow in her footsteps to this day — and delight when they lead us off the beaten track.

Young’s journals reside at The University of Texas at Austin Dolph Briscoe Center for American History.

Dr. Clary retired from her position as the Center’s director of plant conservation in August 2017.