What’s in a Name?

ILLUSTRATION Lisa Gerber

W hen Juliet yearned for Romeo across the abyss of family rivalry, she said, “’Tis but thy name that is my enemy.” Alas, her love with Romeo was not to be: They went to their tragic deaths, caught and separated by a conflict of names. Names have power, and naming is a power. Kiowa writer N. Scott Momaday, in “The Names: A Memoir,” said names sometimes reveal, sometimes conceal identities.

I’ve thought a lot about names over the decades I’ve taught and litigated about issues affecting Indigenous peoples of this continent. When you come at “Indian” this way, from a historical, legal matter, it is obvious the name is the result of a mistake. Columbus didn’t know where he was. He thought he was going to India and insisted he had arrived, so he named the people Indians. “Native American” is an equally fake name that came into vogue as political correctness. How can a people be “natives” of an entity (i.e., “America”) that they preexist?

Santee Dakota poet, musician and activist John Trudell, with his typical wit, observed, “They change our name and treat us the same.” In short, “Indian,” “Native American” and “American Indian” are not authentic names. To be authentic, we have to inquire into the language of each people to find the name they call themselves. It is not surprising to find that the deepest real names are often a tribe’s word for “people,” or for their homeland.

Trudell put it this way: “We’re not Indians and we’re not Native Americans. We’re older than both concepts. We’re the people. We’re the human beings.” In 1994, Anishinaabe author Gerald Vizenor (whose tribe was named “Ojibwe” by Europeans) ratcheted up the criticism when he said “Indian” is a “simulation in the literature of dominance.” The word perpetuates the original colonizing confusion (and the damage therein).

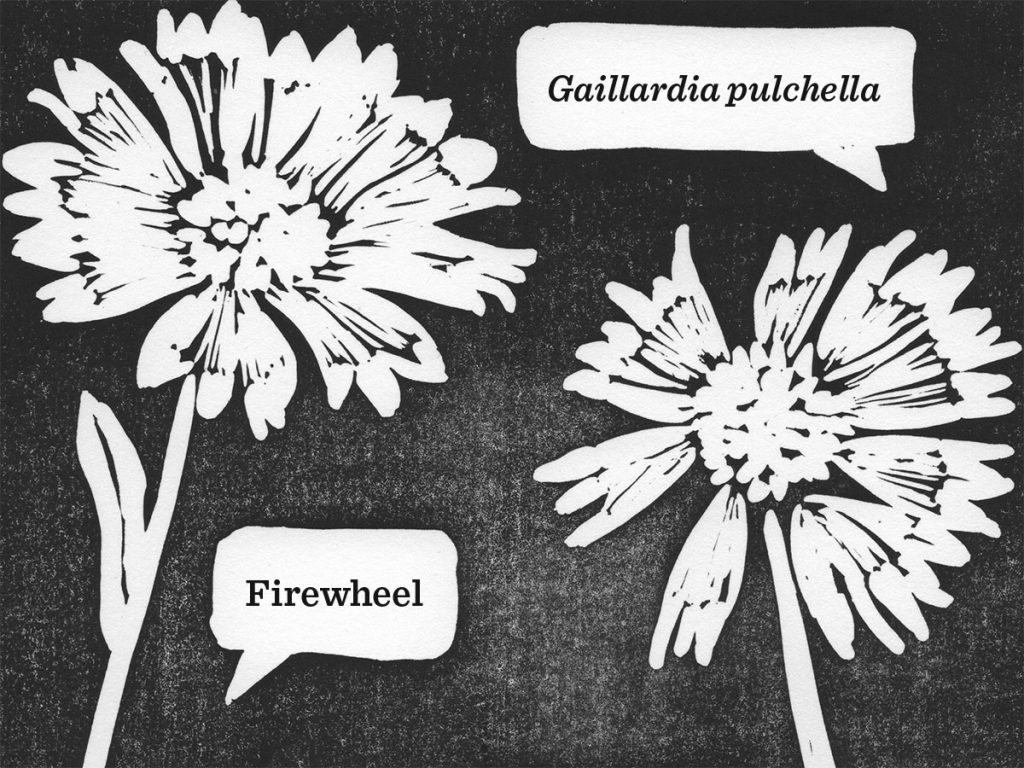

We may not think of colonialism when we use “Indian” to name plants and places across the continent, but the fact of language ties us to that history. Gaillardia pulchella is a good example. The USDA lists the flower as “Indian blanket,” matching common usage. Some people, understanding Vizenor’s logic, reject “Indian Blanket” as a false name. The USDA accommodates, saying an alternative common name is “firewheel.” The Wildflower Center refers to both names and adds the Spanish “girasol rojo” (red sunflower).

There are others, equally appreciative of the flower, who fly into a rage about name changes they perceive to be about political correctness — or, in the latest iteration, “cancel culture.” There is something to think about there: Changing a name does history a disservice by removing colonial terms, thereby removing from consideration the important topics they raise. An argument toward historical accuracy compels attention to documents and reflection on word origins, whereas revision for feelings or sensitivity is wholly subjective.

One proposed middle ground is continued use of historically erroneous names only with historical and cultural contextualization (an approach recently adopted by The University of Texas at Austin in relation to certain campus monuments). In this case, that approach would list “firewheel” first, followed by “Indian blanket” with an explanatory phrase.

Another way out of this naming battle would be to accept the variety of other names for the plant, not only firewheel, but “beach blanket-flower,” “bedding gaillardia” and just plain “blanket flower.” Perhaps the best way to resolve the conflict would be to bring the warring sides into dialogue (always a good thing), asking each to think about the scientific name for the plant’s genus. Gaillardia was chosen by a French botanist who grew the plant in his Paris laboratory in 1786 from seed gathered in Louisiana to honor his patron, the magistrate Gaillard de Charentonneau. What does that name have to do with authenticity, native or otherwise?

Similarly, Linum lewisii is the scientific name for a blue flax, named after Meriwether Lewis, who gathered it along his expedition. His partner, Clark, got two namesakes: Clarkia amoena and C. elegans. The point being, if we widen the discussion, we’ll see “political” aspects in lots of plant names that don’t involve “Indian.”

Strange as it seems, wildflower names do bear the burden of Columbus’ confusion, raising historical questions about natives, immigrants, invaders and colonizers. Wildflowers can provoke awareness of history and culture. To speak of “Indians” is to participate in colonialism (even if one speaks of oneself). To reshape our vocabulary is to confront history and all its imperfections in the present — where else can it be confronted? At the root of the matter is an ontological question: Who are we?

What better opportunity to do this very difficult work than by sharing our appreciation for the beauty of a wildflower? As a bonus we come to realize beauty is beyond the power of words to define, but that words are all we have, and we must use them wisely.