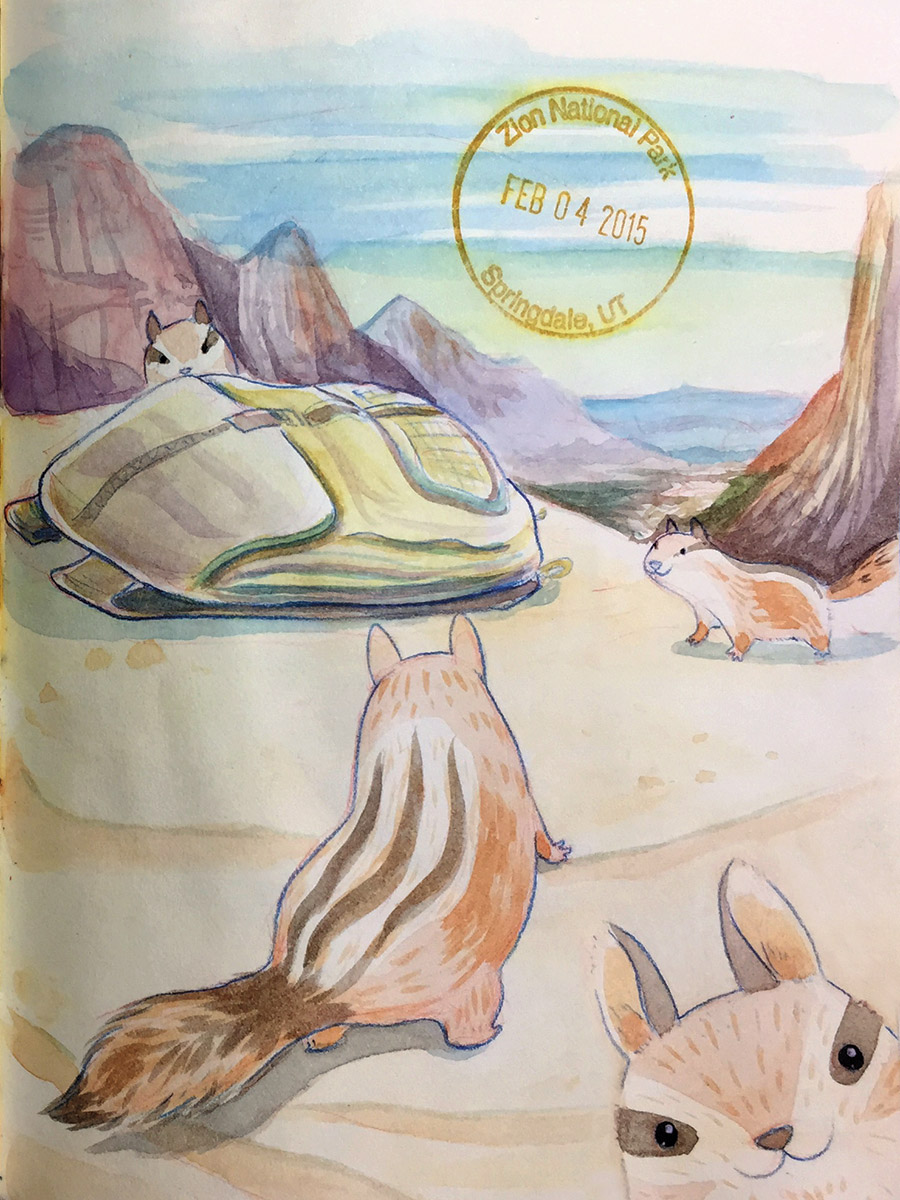

Nature Redux

ILLUSTRATION Joe Feliciano

My family’s road trip in the summer of 1990 had the makings of an epic adventure: four people in a 1985 Dodge Caravan and a plan to visit several of California’s National Parks in two weeks. I was 7 years old, with a wicked perm and a thirst for knowledge. My 10-year-old brother was obsessed with fish. My father, an engineer from rural Michigan, was itching to record wild animals with his new, state-of-the-art camcorder. My mother was promised many a night’s stay in luxurious, beautiful lodges.

Best laid plans, of course. Our Caravan’s air conditioner broke while driving through Death Valley. My brother’s interest in fish proved limited to tropical ones he could keep in a tank. The lodges, to my mom’s chagrin, were two-star motels. My dad, however, did spend three hours parked in the same spot filming a single moose drinking water. We finally drove back to our home in Orange County, California, three days early, overheated and exhausted.

That trip was the last time I would visit a National Park for 25 years. To my 7-year-old mind, spending time in nature meant people were going to be miserable. My parents seemed to feel the same way. We spent the remainder of my childhood summer vacations at a hotel in San Diego, 50 miles south of our house, swimming in pools, sitting on the beach, and sleeping in clean beds.

I was 7 years old, with a wicked perm and a thirst for knowledge.

From then on, nature and I had an uneasy alliance. Thanks to some very patient friends and boyfriends, I went camping a handful of times and braved a few hikes. I knew that Washington, where I moved in my 20s, was full of National Parks, but I hadn’t visited any. When I spent time in nature, it was to make other people in my life happy — not be- cause I really wanted to.

Then I learned I could become a Junior Ranger.

In the summer of my 32nd year, my husband, two friends and I took a road trip from my home in Seattle to Deadwood, South Dakota. It was my friends’ idea, my husband was excited, and I was promised there would be no camping — only tourist traps and Airbnbs. And I’d grown to like traveling. My perm had long grown out, but my thirst for knowledge was ever-present. I wanted to learn about the weird wonders of America by visiting Wall Drug or petting a prairie dog. But I had no plans to seek out and explore the wilderness.

ILLUSTRATION Joe Feliciano

On our way to Deadwood, we stopped at Little Bighorn National Monument and Battlefield, a historic site run by the National Park Service. (There are 417 such sites in the U.S.) It was interesting enough to look at: a huge national cemetery, an obelisk, and tons and tons of open field where the battle took place. After about 15 minutes of staring at all that land, I wandered into the gift shop, feeling a little bored. I saw two kids about 10 years old, standing in front of a park ranger, adorned with badges and reciting a pledge. I was captivated. I wanted what they had.

It’s not hard to become a Junior Ranger: Anyone of any age can get a Junior Ranger booklet at almost any Park Service visitor center. The booklet is a scavenger hunt around the park site; some are more challenging than others — Yellowstone suggests you take three days to finish because there are so many parts of the park to visit — but it’s designed for kids ages 6 to 12. When you’re done, you take the booklet to a park ranger and they give you a badge.

But to earn that title — my first — from Little Bighorn, I had to walk around all that open land. I had to look at plants and draw pictures of them. I had to be outside, in nature, and interact with it.

I did. And I loved it. I kid you not when I say that I’m a proud Junior Ranger at 38 park sites across 10 states. I’ve hiked in and out of Carlsbad Caverns when the elevator was broken. I’ve climbed to the top of a gypsum dune at White Sands. I’ve hiked 3, 6, 10 miles — sometimes even in the snow.

While the badges are great, they’re not the reason I do it. I get to feel like I’m a kid again, only this time it doesn’t matter if the air conditioner is broken or if the fish are all swimming too fast or a moose hasn’t moved in hours or a hotel wasn’t nice enough. It’s just me, a booklet and a beautiful place to be.

Paige Richmond is an educator who specializes in teaching students with emotional and behavioral disabilities. Her writing has appeared in Seattle Weekly, City Arts, The Seattle Times, Seattle Sound Magazine, the Inlander and more.