Plant Some Rubber

You’ve probably thought about supply chains more than you ever hoped to this year. Whether dog food or toilet paper was running low, how we get things — and how people become innovative when necessary — are top of mind whether we like it or not.

Native plants have come to the rescue over the course of U.S. history in many unsung and perhaps unknown ways. From filling life preservers during world wars to building formidable ships, native plants are often saviors at trying times. Disruption (and, yes, necessity) has led to invention.

One of those plants has stepped up to pinch-hit in such circumstances, time and time again. Yet it continues to be left on the table — or in the desert, as it were. Now, it could be a new beginning for the United States’ domestic natural rubber supply.

ILLUSTRATION Drue Wagner

Riding On It

Chances are, you’ve never heard of guayule (Parthenium argentatum), a perennial shrub with small, yellow-white flowers and gray-green foliage resembling that of sagebrush species (they’re all in the aster family). Guayule is native to the deserts of Mexico and four counties in the Big Bend area of Texas: Presidio, Brewster, Pecos and Terrell.

Despite its lack of notoriety, this seemingly modest native plant has a rich history in the United States, and it could have a bright future too. Guayule (pronounced “why-YOU-lee”) also goes by the name “rubber plant,” a reference to its latex content. Latex is the raw material used to make natural rubber; it is typically tapped from rubber trees (Hevea brasiliensis) in a process not unlike harvesting maple syrup.

Though H. brasiliensis trees are native to South America, 89% of Hevea-sourced rubber comes (rather inexpensively) from plantations in Southeast Asia. Wondering how much rubber comes from the United States? Zero, zilch, nil.

That’s pretty astounding considering Americans use natural rubber for thousands of everyday items, from erasers and pacifiers to rubber bands and balloons. “No other critical material or food only has one source,” says Dr. Katrina Cornish, an Ohio State University researcher who’s been studying alternative rubber and latex production for over 30 years. “It would be like a potato famine meaning that there are no carbohydrates now.”

The most significant product that uses natural rubber is tires. Car, truck and bus tires are made of 50 to 100% natural rubber; bike tires and shoe soles all contain natural rubber; and airplane tires are entirely made of it (airplane tires made of synthetic rubber, which is less durable, flexible and heat tolerant, would likely explode upon landing). That means natural rubber takes you pretty much everywhere you go, regardless of method.

Of course, we’ve all lessened our travel in the past several months, which Cornish says is actually a good thing when it comes to America’s rubber situation. “People are staying at home; they’re not wearing out their tires,” she says, explaining that we’d be “in dire straits” if that weren’t the case because natural rubber from Hevea trees was already running out.

Our current source of natural rubber faces numerous threats: Climate change is constricting the area suitable for growing these trees. Clear-cutting rainforests to make room for rubber tree cultivation, thankfully, is being halted due to deforestation moratoriums such as those sponsored by the World Wildlife Fund. And devastating diseases such as South American leaf blight have the power to take out entire forests.

Because cultivated Hevea rubber forests are cloned, they are genetically identical across miles of trees, which leaves them no ability to fight such diseases as individuals. They are also planted very close together, so leaves and roots are all in contact. Leaf blights are essentially a death sentence. In other words, our natural rubber supply, on which many products rely, is far from secure, which is why Cornish claims we are facing a “pending rubber apocalypse.” It’s not a matter of if, but when. “It’s inevitable that it’s going to happen,” she says.

This is where guayule, our understated Texas native, comes in. There are roughly 2,500 plants that produce latex and can be used to make natural rubber, but Cornish says most “don’t make the sort of rubber we need.” To compete with Hevea-sourced rubber, the result has to be high quality and the source farmable. Guayule offers both.

ILLUSTRATION Drue Wagner

Like a Glove

The major use Cornish envisions for guayule rubber — which is made from the tops of plants and can be harvested again and again from the same crop — is in medical products such as gloves, catheters and condoms.

Guayule rubber offers some impressive upgrades as a medical material: It doesn’t contain the proteins in Hevea-sourced rubber that many are seriously (even life-threateningly) allergic to. In fact, guayule is the only nonallergenic natural rubber option. And it plays well with others. Because it’s remarkably soft, strong and stretchy in the first place, Cornish explains, you can blend it with other components and still end up with a thin, supple glove. “It’s a really spiffy polymer,” she says.

Her team has successfully combined it with bismuth trioxide, a radiation-resistant substance that results in gloves able to protect wearers from both disease and radiation. Surgeons who need both currently wear two pairs of gloves at once, which she likens to getting an operation by someone wearing boxing gloves.

Cornish recently submitted a funding application to the USDA’s COVID Rapid Response Research Program to create ultrathin, uber-protective guayule rubber gloves. When asked if her work feels more relevant than ever, in light of supply chain issues and the demand for personal protective equipment, she says, “Absolutely.”

For guayule to become a true commodity, however, it needs to be incorporated into that big rubber industry: tires. Doing so would require millions of acres to grow the plants on, infrastructure, processing facilities, and research and development.

Tire companies such as Bridgestone and Cooper have begun exploring their domestic options; the former is operating research stations in Arizona and partnering with University of Arizona and U.S. Department of Agriculture researchers to develop guayule-sourced rubber. They created their first guayule-rubber tire in 2015, but the product is not yet commercially available.

As Cornish puts it, “You can’t jump from nothing straight into tires.” So she’s trying to make a name for guayule rubber in the niche glove market first. To that end, she is CEO and chief science technology officer at her own biotechnology start-up, EnergyEne Inc. Though they currently get their guayule shrub supply from Arizona, they are looking for new land and new sources, including field sites at Texas Tech. She hopes to be able to work with tribal nations in the Southwest and utilize retired cotton farms as well.

ILLUSTRATION Drue Wagner

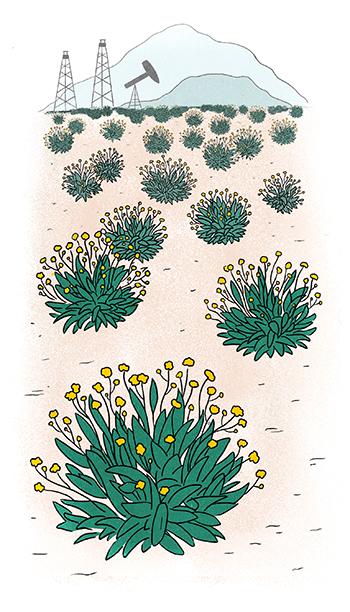

Home Grown

Speaking of Arizona and Texas, guayule is a desert plant. Besides creating what Cornish calls, simply, “a wonderful material,” it could also be a sustainable domestic source. Evergreen guayule thrives in environments with poor soil, full sun and little rainfall. And land to grow it on could come relatively cheap.

Tommy Roach, owner of Noircroxx Biological and Dr. Cornish’s project coordinator in Texas (a post he describes as “hunting land” and “running around trying to help for the last five years”), agrees. Roach says land for growing guayule — which he’s scouted and soil-tested for miles around Marfa and the Davis Mountains — goes for about a third of the cost per acre that one would pay for potato or alfalfa farmland in Texas’ High Plains. Plus, he says guayule “likes that area,” noting that the soil, dry air and micronutrients are compatible, and there aren’t any pest or disease problems of note. Another advantage Roach mentions is that you can grow it on oil land right up to the rigs because, unlike other crops, “You’re not gonna consume it.”

Cornish and her colleagues are also researching a dandelion species native to Kazakhstan (Taraxacum kok-saghyz) that produces rubber in its roots. It needs moist, fertile conditions to grow outdoors, but its best setup for high rubber yields comes from hydroponic cultivation. In either case, guayule is low maintenance by comparison.

Some means of production already exist. To extract latex from guayule, the harvested tops of plants are put into what is essentially a giant blender, then “immersion ground” in water, which releases the rubber particles. These are skimmed off the top, not unlike skimming cream from milk. Cornish says “We actually use a hot-milk separator” (a type of centrifuge used in the dairy industry), indicating that guayule rubber production could easily take advantage of existing methods and equipment.

Growing latex-producing plants and moving natural rubber production home could also bring an enormous amount of agricultural and manufacturing jobs to the U.S. In the long game, Cornish says we could eventually be a rubber exporting country. With all these advantages and the security that inherently comes with controlling our own supply, why does the U.S. keep importing natural rubber? It’s simple: money and inertia.

Burning Rubber

Guayule has resurfaced and disappeared throughout American history. “If it wasn’t for politics,” says Cornish, “we’d have a thriving domestic guayule industry now.”

It’s not hard to believe her. Cornish seems to know everything about guayule. In a half-hour conversation, she brings up a famous surfer known as the “Guayule Kid” (Phil Edwards), references a 1950s stock deal involving (an almost-defunct) Intercontinental Rubber Company and Texas Instruments, and mentions a failed guayule crusader (Hugh Anderson) who she’s afraid to end up like. She even recalls a bad novel someone passed along with a plot revolving around leaf blight terrorism. That may seem like a ridiculous storytelling device, but guayule actually has a past filled with geopolitical intrigue.

In “Growing American Rubber,” author Mark Finlay writes that guayule originally gained attention after a Mexican display featured it at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. Italian and German chemists became interested, fueling a competitive boom in the United States from 1900 to 1907. Interested parties included such well-known names as Thomas Edison, U.S. Senator Nelson Aldrich and John D. Rockefeller. In 1906, The New York Times reported that Aldrich and Rockefeller obtained options on all guayule rubber manufacturing plants in Mexico in an effort to “syndicate the guayule industry.”

“If it wasn’t for politics, we’d have a thriving domestic guayule industry now.”

But the plant’s true moment in American history was during World War II, when Congress passed a law forming the Emergency Rubber Project in 1942 (Finlay calls it “the Manhattan Project of the plant sciences”). Its goal was to establish a domestic rubber source after Japan cut off 90% of the world’s supply in Southeast Asia. This included tens of thousands of acres of land being devoted to guayule growth and research in California and the Southwest — a great many of which were at Manzanar, a Japanese-American internment camp in California.

In his paper, “The Role of Botanists during World War II in the Pacific Theatre,” former Arnold Arboretum director Richard A. Howard writes: “It has been said that no nearer complete or better coordinated organizational plan had ever been prepared in government.” The project was put on hold, however, to prioritize food production — and ultimately called off in 1945. It produced 1,473 tons of rubber, but the plantations and seeds were ultimately destroyed (along with over 10,000 tons of rubber), leaving guayule underexplored for another few decades.

Cornish and Finlay both identify racism as another reason the project was liquidated: Americans didn’t want to give credit to Japanese-American scientists for their discoveries. So they (literally) burned it and put their money on synthetic rubber, which Cornish says has never been able to perform like natural rubber.

American interest in guayule was briefly rekindled in the world oil crisis of the 1970s, which incentivized finding naturally occurring substitutes for synthetic polymers. History really does repeat itself. But guayule, with all its promise, has never truly taken hold. As Finlay writes, “Government officials continually rebuffed, for nearly thirty years, efforts … to develop guayule as a new American crop and strategic resource.”

All of these efforts were embarked upon in order to decrease U.S. dependence on foreign natural rubber sources, a problem we still very much have today — a problem Cornish is working hard to solve.

When asked if another disaster is necessary for guayule to finally make progress, Cornish says, “I hope it doesn’t come to that,” adding, “You need to establish it so you can be commercially viable in a normal economy.” But she is also the one giving Ted Talks on a forthcoming rubber apocalypse. The thing is, she wants the U.S. to beat a rubber crisis to the punch for once.

In order to do so, guayule needs land, infrastructure and research, but it also needs that thing every cause does: “somebody with a vision who’s also got money,” as Cornish puts it. With four significant investor groups looking into her research, she feels hopeful for the plant’s future. “It’s all ready to go,” she says.

In the Lone Star spirit, Texans might say come and take it — or, better yet, come and grow it.

Honorable Mentions: Two more unsung plant heroes

ILLUSTRATION Drue Wagner

Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Common milkweed happens to be one of the 2,500 plants that contains latex (and it has also been explored as a domestic rubber source), but its claim to wartime fame has to do with life jackets. During World War II, milkweed fluff — seeds outfitted with silky parachutes (or “comas”) for wind dispersal — replaced fibers that typically came from kapok (Ceiba pentandra) trees, a massive tropical species. Exports to the U.S. (and Canada) dwindled after Japan gained control of Indonesia, and North America needed a domestic source of buoyant stuffing.

“In 1942 or ’43, when I was in grade school in central Pennsylvania,” says Wildflower Center member and volunteer John Irwin, “we were given a day off school to go out in the woods and collect milkweed pods for life preservers.” His collection was part of a larger effort across the country to fill the vital vests. As Joe Marcus, coordinator of the Center’s Native Plants of North America database, puts it, “It’s hard to imagine today how virtually the entire country pulled together between 1941 and 1945 for a common goal.” But it did. And many sailors reportedly owe their lives to the effort.

ILLUSTRATION Drue Wagner

Candelilla (Euphorbia antisyphilitica)

Native to the Chihuahuan Desert of Trans-Pecos Texas, New Mexico and Mexico, candelilla yields a high-quality wax that has been useful throughout North American history, particularly in times of war. Its stems have a waxy coating (a water-conservation adaptation of many desert plants), which can be harvested by boiling plants with sulfuric acid, a historic industry along the Rio Grande.

While candelilla wax has been used in products from shoe polish and candles to chewing gum, records and soap, its waterproofing ability made it a valuable military supply during both world wars. In “Coyame: A History of the American Settler,” Dr. Francisco Javier Morales Natera describes its military uses as “countless,” listing waterproofing airplane wings, tents and tarps among the most common. Candelilla wax has been commercialized since the early 1900s, but demand increased circa World War I, when the supply of imported vegetable waxes declined. Wars (and pandemics) lead to all sorts of needs, and native plants often come to the rescue.