Love Letters

“Plants unify people from all walks of life,” says Dr. Mallika Nocco, a conservation biologist and co-founder of Plant Love Stories. “You can love plants and have any sort of political identity. You can love plants … from anywhere in the world.” It’s true: Plants — and plant love — are universal and inclusive. And Plant Love Stories is on a mission to cultivate that love online, at science conferences and live storytelling events, and via social media.

The brainchild of eight David H. Smith Conservation Fellows — postdoctoral researchers who specialize in topics from tallgrass prairie restoration to community fishery programs — Plant Love Stories grew out of a conversation in a hotel conference room when the founders “were maybe a little bit burnt out from discussing how to impact policy,” according to Dr. Caitlin McDonough MacKenzie.

As the PLS team recalls, ecologist Dr. Rebecca Barak said, “Can’t we just do something fun?” That something took the shape of an online forum devoted to recognizing that plants are, intrinsically, part of each of our personal histories.

“We do get to have fun,” says Barak of the resulting project, “but we’re also connecting with people on an emotional level. We’re really thankful that people are willing to share those stories with us.” The founders of PLS believe everyone has a plant love story, even if they don’t think they do. And their submissions so far reveal a wide variety of voices, endless reasons for loving plants, and a hodgepodge of beloved subjects. Let’s read a few that highlight native plants. After all, it’s not every day that you get to sneak a peek at someone else’s love letters.*

*All stories have been shortened and/or slightly altered.

A Family & Food Story

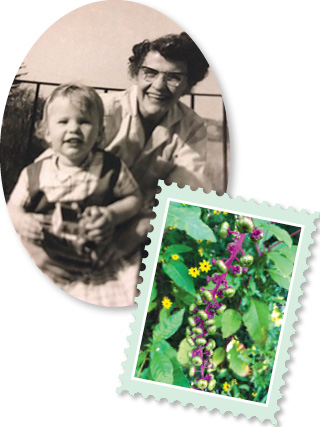

From: “Pokeberry Sprouts for Dinner” by Cheryl Moorhead Stone

Featured native plant: American pokeweed (Phytolaca americana)

MY GRANDMOTHER, GRAMMY, was a back-to-the-earth hippie decades before the actual movement started in the 1960s.

Diminutive in stature, Grammy embodied grace, determination and intellect. Her laugh was a melody. She loved nature and was happiest on a walk where she would be observing and commenting on things she saw. These excursions began when I was six years old and continued throughout my childhood.

When we headed out in search of particular plants or mushrooms, we did so with the intent of serving them at dinner. Fiddlehead ferns, teaberries, wild strawberries, mushrooms, watercress and poke are some that come to mind.

My lessons on pokeweed spanned the growing season. Early on, she took me to a clearing at the bottom of a pine-covered hill where the pokeweed grew in plenty, explaining that the plants came back every year in the same place. They were perennial. She said that we needed to wait to pick them until the sprouts formed leaves but before the plants grew tall, when the leaves would become increasingly bitter and ultimately poisonous.

When the sprouts were maybe 10 inches high, we harvested them. Grammy said it took a lot of leaves because they would cook down. Our brown paper sack full, we hiked back to “camp.”

We washed the greens and placed them into a big pot of boiling water heated on the wood-burning stove. After cooking them for a bit, the hot water was poured off, greens set aside, and new spring water heated. Grammy said it was best to follow this procedure.

When the water was boiling, we added the much-reduced volume of greens to cook once more, but not for long. Drained once more, Grammy put the greens into her cast iron frying pan, where some of the morning’s bacon grease remained, and tossed them around until they were “just right.” She added a sprinkle of salt and pepper and served the plates.

None of the other kids knew all the secrets I’d learned about fixing poke. Grammy provided a wonderful dinner and an empowered granddaughter who, at 65, now gets to teach her own grandchildren lessons about nature, cooking and love.

A Love & Loss Story

A Love & Loss Story

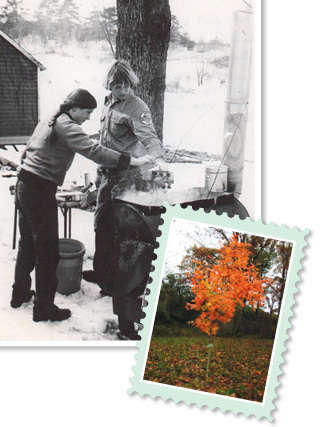

From: “A Triad Romance” by Charles W. Bier

Featured native plant: Sugar maple (Acer saccharum)

I DON’T KNOW WHEN I first began to really know trees. As a youngster, I was literally a snake-in-my-pocket sort of kid. I was blooming as a broader young naturalist in my later elementary years. By the time I was a high school freshman, it was clear that I was falling in love.

My new love was especially beautiful in spring and fall; a member of rich, moist, climax forests and just rare enough in my life that I would often be scanning the landscape for her whenever I was out. And my love was the sweetest. That is probably what really clinched our relationship, for my love was the sugar maple (Acer saccharum). I consummated our relationship late in the winter of my 15th year when I taught myself how to make maple syrup.

Meanwhile, a biology teacher took me to a special place, a place where my love would profoundly blossom. It was Todd Sanctuary, land protected by the Audubon Society. My first love was there, tucked away in cool and not-too-acidic soils. Then, dumbstruck, I was hired to conduct research and lead nature walks in this forest sanctuary while I was in college. There was a crude cabin there where I lived. For me, it was heaven on Earth.

On an early June day, I went to meet a group for a scheduled nature hike. I remember immediately being drawn to a young woman with a strikingly sincere face and a long braid of hair down her back. Terry and I met that day, and she seemed genuinely interested in what I had to share about the forest. She was a farm girl at heart but interested in what was all around, and I could again sense some sweetness in her.

Some months later I traveled to the valley where she was living, a tributary of Buffalo Creek. I reintroduced myself and wondered aloud if she had ever considered tapping the sugar maple trees in her valley and making maple syrup. In what is now a classic family quote, she said: “I would tap those trees and make syrup, if I only knew how to identify a sugar maple.” But my god, that was one of my specialties, and we joined forces to produce maple syrup, a garden, and take lots of nature hikes. She taught me how to milk her cows, and we continued to be in awe of the sugar maple whenever it was in bloom, in golden autumn splendor and certainly when the sap was running. It was a courtship triad of sorts.

Terry and I were married in January 1981 and continued mapling together for many years to come as we started a family and established a homestead on nearby land where maples also grow. Terry passed away in the winter of 2009. The following spring a sugar maple tree was planted in Terry’s memory at her church.

A Scientist Origin Story

A Scientist Origin Story

From: “The Defender of Plants” by Matt Candeias (of In Defense of Plants)

Featured native plant: Wild lupine (Lupinus perennis)

THE FIRST TIME I SAW LUPINE BLOOMING IN THE WILD, a blanket of purplish-blue flowers swaying softly, covering an Indiana dune, I had to sit down. We had just come through a clearing in the trees, following a trail down to the lakefront that allowed us to hike through 10,000 years of dune succession in a single afternoon. I saw the blue spikes off in the distance, but until I came to them I didn’t realize what I had been seeing. The view was stunning.

Wild lupine and I have a past. Lupines were the in-between step that led me from being an excited, science-loving undergrad without a real plan to a botany graduate student today, and helped inspire my development of In Defense of Plants, a blog, podcast and social media presence spreading plant love.

My final semester of college, I took a restoration ecology course where everything began to fall into place. I realized that people can actually get jobs repairing ecosystems. That realization changed my trajectory.

Soon after, I was hired by a mining company to help with a pit mine restoration project in western New York. In a typical mine reclamation, a retired strip mine is covered with topsoil and grass seed. But this company wanted to do better — they had decided to focus on butterfly restoration through trying to restore the butterfly’s host plant, wild lupine.

I realized that people can actually get jobs repairing ecosystems. That changed my trajectory.

We started planting lupine seedlings into the ground that was dotted with grasses. Most of the lupines we planted did not establish, but some did!

We were trying to figure out how to get more lupines to thrive. In a leap of faith, I reached out to a scientist who studied plants. We figured out that some of the existing grasses were helping the lupines by creating microclimates that support their growth. We finally had the missing pieces of the puzzle to make this a successful restoration project.

Years later, in a totally different habitat, I saw them again. In the Indiana Dunes, wild lupine has been part of a major conservation effort for years. In the Great Lakes region, lupine restoration and conservation is linked to the federally listed Karner blue butterfly. But as I have discovered over and over again, no matter what aspect of the community we are trying to conserve, it can always be traced back to the plants.

A Love-Hate Story

From: “The Allergy Tree” by Mark Brunson

Featured native plant: American linden (Tilia americana)

I LOVE TREES, but trees don’t always love me. The trouble is: I’m susceptible to pollen allergies, and those allergies are always worst in springtime when trees are the primary culprits.

Being only moderately allergenic, I’m not entirely sure why the American linden has elicited my greatest ire over the years. Maybe it’s because by the time the linden blooms, I’ve endured three months of sneezing and am at the height of my allergy frustration.

One tree in particular has drawn my antipathy over the years: a large and robust specimen in the courtyard of the Utah State University campus building next to mine. I called it the allergy tree. Not only did it make me sneeze, but also it was my pollen barometer. I knew that when its blossoms began to fade, I could gleefully put away my Claritin for the season.

Last week I heard chainsaws outside my building. I looked out to see men cutting down the allergy tree to make room for a renovation. And I’m surprised to find that it makes me very sad. It wasn’t the tree’s fault that its pollen made me sneeze, and it wasn’t the tree’s fault that it grew so big and healthy that it got in the way of construction crews. I’ll surely find another linden to use as my barometer, but it won’t do the job as well. I guess that just means love of trees is as complicated as love of people.

A Climate Change & Culture Story

From: “Tundra Cloud(berrie)s” by Briana Jasinski

Featured native plant: Cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus)

I WAS FIRST INTRODUCED TO CLOUDBERRIES via the name of a man-made structure: a (now-closed) bed-and-breakfast called The Cloudberry in Fairbanks, Alaska. Its wooden turrets rose up like an enchanted castle above the stunted boreal black spruce forest.

It was used as field housing [on] my first botany technician job. Little did I know, the cloudberry would recur in my life, over and over — in the form of a small plant.

The cloudberry (aka bakeapple or salmonberry) is widespread across the arctic. It is a sweet, soft, dreamsicle berry, with a muted taste reminiscent of oranges, cream, tart fruit and a hint of salmon. When ripe, it fades from a bright pink to a translucent, creamy orange that smears apart on your taste buds.

My first cloudberry was eaten while sitting on the pink styrofoam seat of The Cloudberry’s outhouse toilet in midsummer. After watching a small berry ripen in front of my face for a week, I selfishly plucked it and popped it in my mouth.

A few years later, I tasted akutaq for the first time, or “Eskimo ice cream,” a chilled mixture of Kuskokwim sheefish (whitefish), Crisco (originally seal fat) and vitamin C-rich cloudberry. [It’s] cold, sweet, savory, slightly fishy and chock full of calories — the perfect traveling food for exhausted subsistence hunters.

Now, as a graduate student studying arctic ecology, the cloudberry has come full circle to haunt my thesis. I study how individual plant species are reacting to deepening permafrost thaw resulting from climate change. Specifically, whether that newly thawed soil horizon is providing plants with a new, rich source of nutrients that hasn’t been available since the beginning of the last ice age — and whether or not their little rootlets are getting those nutrients. I [have] experienced the cloudberry in the way that only a plant ecologist can: over the course of 136 hours of hand-plucking their roots with tweezers from chunks of soil.

The connection of this beautiful, delicious plant to the changing arctic landscape and the humans that inhabit it is fascinating. As thaw boundaries continue to deepen and arctic roots stretch into newly revealed soils, I’m fascinated to see what the arctic has in store for this deliciously creamy berry. Maybe more pies.

A Native Plant Gardening Story

From: “Oh Where, Oh Where, Has My Monkeyflower Gone?” by Kathy Kuebbing

Featured native plant: Bush monkeyflower (Diplacus aurantiacus)

AT THE YOUNG AGE OF 60 YEARS OLD, I decided to take on a monster gardening project. After retiring to the beautiful Oregon coast and having more time to spend in the yard, I decided to transform a very weedy and ugly hillside into a native garden. Eight years later, I am amazed at how much change has occurred and how much fun I had along the way.

I first learned that the hillside had three different growing zones! I started with the sunny side, and selected three Nootka roses (Rosa nutkana) to plant in my first plot. Next, I decided only the native Salal berry bush (Gaultheria shallon) would be able to hold onto the steep hillside.

The wetland gave me the most challenge. My first attempt at adding color was with the addition of a yellow monkeyflower (Diplacus aurantiacus) during the rainy season in late November. Unfortunately, I did not mark the place where I planted my lovely monkeyflower, and for the next two years I searched relentlessly to find the yellow in my wetland. It was not to be. I had lost my monkeyflower.

That was not my last attempt at adding color, but I failed many more times before I realized that green is a beautiful color. Today, lovely green mosses and ferns adorn the wetland.

When I began this project, I had no theory of what would happen. I just [hoped] I would not need to hire a professional landscaper to clean up any disaster I might create. But I did discover something unexpected halfway through the project. Once the hillside filled with more native plants than weedy plants, I would find native plants choosing the hillside garden as their home.

One year thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) showed up and then a gooseberry (Ribes sp.) moved in next door to the thimbleberry. Brackens (Pteridium aquilinum) decided the wetland needed a slightly softer color of green than the dark green swordferns (Polystichum munitum) I planted in the area. Native flowers populated the slope from time to time, my favorite being the fringe cup (Tellima grandiflora). Now my hillside project is done, but years into the future I will enjoy visiting it to find what new native plant or flower has decided to join the community.

Best of all, I purchased two more yellow monkeyflowers after my hillside project was complete. I upgraded these plants to the formal gardens in my backyard and put signs around them to remind me of where my lovely monkeyflowers would forever grow.

An Endangered Plant Story

An Endangered Plant Story

From: “With Love, From the Mojave Desert. Meet the Amargosa Niterwort” by Naomi Fraga

Featured native plant: Amargosa niterwort (Nitrophila mohavensis)

WHEN I FIRST HEARD ABOUT PLANT LOVE STORIES, I had one thought. Must follow! I wanted to contribute, but I had a huge dilemma. Which plant love story do I tell?! So I narrowed it down to my current love affair with the one, the only, Amargosa niterwort (Nitrophila mohavensis).

The Amargosa niterwort is a rare plant in the goosefoot family (Chenopodiaceae), and it has a lot of special requirements. It lives on salt flats near Death Valley, in one of the hottest, driest places on earth, but the niterwort is a water-loving plant. It lives in an area with a high groundwater table that is relatively salty, but the niterwort doesn’t like it too salty. If the available water in its habitat is reduced, then that makes it more salty, and that is not good for the niterwort.

My relationship with the niterwort runs deep. I visit it every month to monitor its growth, and that means I have a fairly good understanding of the extreme environment it lives in. From 50 mph winds to over 120-degree heat, this plant rolls with the punches. It is also federally listed as endangered, which means it needs our help.

I’ve made it my life’s mission to save the niterwort from the threats it faces. It is an incredibly unique plant. There are only two species of Nitrophila in the world, and this one lives in a tiny corner of the Mojave Desert. It is a relict from a wetter time, but it is still holding on because this part of the desert has water, and that is a special thing.

I have intimate relationships with many plants, but the niterwort holds a very special place in my heart. With each plant relationship I develop, my commitment to them grows deeper. I do my best to say it loud and proud, but plants matter, and I live my life by that motto. They are a gift to be treasured and cared for by everyone.

Read more Plant Love Stories here — and submit your own.