Having A Ball

LOOK IN THE DAPPLED SHADE TREES across the southern half of Texas and you’re likely to find exquisite little pompom plants known as ball moss attached to the limbs. Look further and you might also find this native Texas plant affixed to power lines, fences and rock walls. Ball moss’s versatility comes from its unique ability to harness all the nutrients and water it needs from the air.

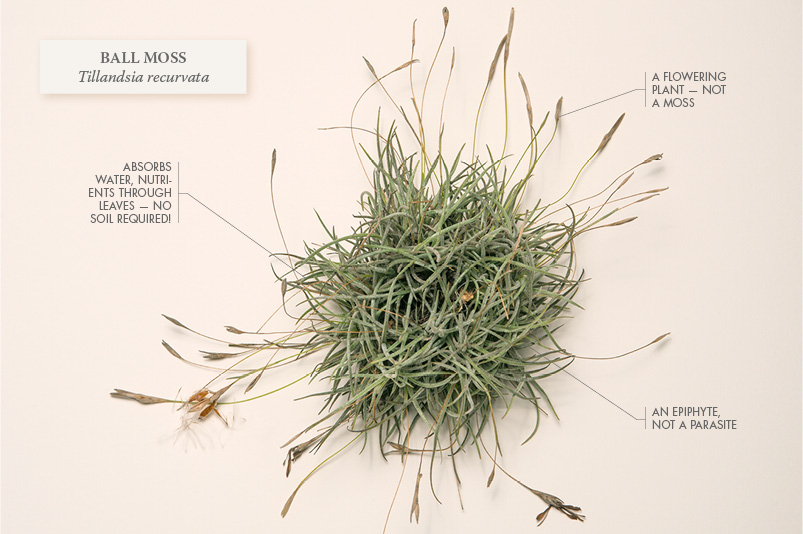

Tillandsias, also called “air plants,” are having their moment right now – look for them in hip terraria and placed just so on mod coffee tables across the country. Ball moss (Tillandsia recurvata), however, remains on many folks’ list of pesky plants, and some still assume they are parasitic.

All William Niendorff sees in ball moss is the future.

“I’m fascinated by ball moss physiology, ecology and their untapped potential in the Texas landscape,” says the landscape designer. “They have unique characteristics that make them space-saving, hardy, easily attachable and water-absorbent plants for growth in the air.”

Niendorff started considering how these rootless plants that don’t need soil could work in designs while a student at The University of Texas at Austin. Ball moss seemed ideal for vegetated roofs, where the weight of soil is an engineering challenge. He found the perfect space to study them at the Wildflower Center, where staff have been studying and developing green roofs for hot climates for more than a decade.

Landscape designer William Niendorff stands next to a structure he’s using to study ball moss for green roofs. PHOTO Joanna Wojtkowiak

Green roofs in Texas and the Southwest are particularly challenging because high temperatures require more of soil and water to keep roots cool and plants thriving. To study the capabilities of ball moss, Niendorff constructed 6-foot-tall structures that look like baker’s racks filled with trays of the fuzzy orbs. The structures hold about 700 plants in layers of hog wire. Gauges check temperatures every 15 minutes. To work for green roofs, T. recurvata will need to regulate temperature better than standard roofing materials while handling harsh rooftop conditions.

He’s also investigating plant mortality. “Because ball mosses grow naturally in the dappled light of the tree canopy, I want to see what types of densities they can tolerate in a green-roof setting,” he says.

So far, Niendorff has confirmed that this member of the bromeliad family (which includes pineapples) is extremely hardy. Despite no irrigation since his six-month study began, a time that included a full hot Texas summer, few plants have died.

“I hope this ecological design project can help unveil the unknown about Tillandsia recurvata,” says Niendorff. “Its full story is yet to be told.”

If ball moss succeeds on green roofs, the flowering plant could be tapped for its ecosystem services in urban environments, such as providing insulation, habitat and lowering the heat island effect, while also improving aesthetics.

Stay tuned. Perhaps ball moss is about to have its moment as well.