A Labor of Landscapes

Author David Todd (left) and cartographer Jonathan Ogren (right). PHOTO Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon

DAVID TODD SAYS HE’S WITNESSED A “MOTION PICTURE OF TEXAS GEOGRAPHY” over the course of his life. During his 57 years, he’s seen the roads around Houston (which had a population of less than a million when he was born) shift from two-lane highways with stoplights to the “16-lane behemoth” that is Interstate 10. “The built world has changed so much,” he says. “The edge of town has always been moving.”

Of course many of us can visualize what he’s describing, but how much better to have an actual map of Houston’s moving periphery? Or a whole slew of maps illustrating urbanization, sprawl, and increasing commuter time and distance? That’s exactly the kind of thinking that results in a book like Todd’s “The Texas Landscape Project,” which tells the conservation history of Texas through both words and maps.

The book’s cartographer, Jonathan Ogren, says, “People like maps,” but that’s not the only reason for their extensive use in the book.

“Maps allow people to see things at scales they couldn’t understand just by us sitting here and talking about [them],” he says. He cites “the relationship between aquifer recharge and urbanization,” “the bison populations in 1880 as compared to 1909,” and “monarch migrations throughout North America” as examples. “Being able to see that geographically represented allows us to evaluate multiple layers and complexity that we couldn’t have before.”

“In a way it’s like a comic book,” says Todd. “The images help illustrate the story.”

Ogren chimes in, calling it a “mashup” rather than an “atlas,” though the term is often used to describe the project. “We cover 40 issues over six big categories [land, water, air, energy, wildlife and the built world], but there’s so much more we could have told.”

He says he and Todd relied on the stories and data that were available but also made subjective decisions, including “what was most intriguing to us and what we thought would be most intriguing to our readers.” It’s certainly not a dry, comprehensive reference book; as Todd puts it, “This has got some propaganda in it.” It’s a collection of pointed conservation stories, wildlife profiles, land and natural resource histories, and images that tell a tale as unique as Texas itself.

The Purpose

“The Texas Landscape Project” is epic. At just under 500 pages, even its index is impressive. When asked what could possibly keep someone inspired and motivated over the course of such an ambitious endeavor, Todd laughs and says, “We’re insane. How much time do you have?”

But the simple answer is change. “We’ve all moved here from elsewhere,” he explains. “There’s a history to this place that was very different. I think that’s worth telling.”

Ogren notes that each of them dedicated the book to their kids, “so it has a lot to do with that” — preserving land and resources for future generations. But he also harks back to his days as the Wildflower Center’s Public Programs Manager (from 1999-2004), noting the importance of “allowing people to interact with the natural world and start thinking about their place [in it].”

“It’s not always in the forefront of our thinking: the environment,” he says. “But it is a basis for how we live our lives and what we’re doing on the land.”

The book aims to help people “understand the unique features of the [Texas] landscape and what our interaction is with them,” says Ogren, “so we can ideally appreciate those relationships, our dependence on this environment, and our incredible interaction with it.” Todd and Ogren also hope it will get people asking how they can help take care of the environment and be stewards of it going forward.

Though quite different in execution, the book acts as a companion piece to “The Texas Legacy Project,” an oral history book and archive that Todd created with videographer David Weisman. Todd describes its content as “heartfelt and true in a soul-rooted way,” but he recognizes that oral histories are often seen as very subjective. “The Texas Landscape Project” takes a lot of similar ideas about sustainability and respect for ecosystems and supports them with data. Todd mostly interviewed non-experts for the earlier endeavor; in a way, he says “The Texas Landscape Project” shows that what those people were concerned with is true. “We can talk about it in conversational terms and we can map it using government data, and we probably come to the same picture.”

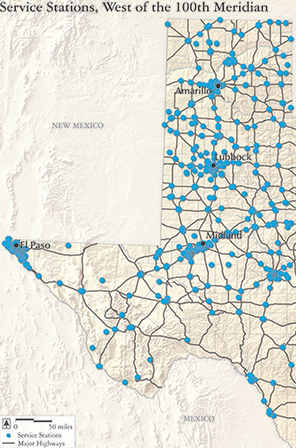

Service Stations West of the 100th Meridian

This map from the Water section of the book was based on Texas Commission on Environmental Quality data showing underground gasoline and diesel tanks. Meant to display how service stations have replaced springs as critical parts of travel through arid lands, Todd admits the concept was “sort of tongue-in-cheek.” But he adds, “There was a real argument there that we’re trying to make that part of environmental history is our increasing dissociation with the environment.” Recalling the writing of John Graves, Todd’s tone is not bitter or preachy. “I try not to be too judgmental,” he says. “I mean, springs are beautiful, ecologically rich places, but for a lot of early explorers, they were like a convenience store; they had a functional use. I don’t think that every soldier who camped there thought, ‘Oh, what a beautiful place this is.’ I think they were probably thinking, ‘Gosh, I’m thirsty.’ We’re not that much different.” MAP Jonathan Ogren

The Plants

Surprisingly, that picture ends up pretty positive from Todd and Ogren’s perspectives. Though they both see population growth and invasive species as challenges, their outlooks are rather sunny when it comes to the future of Texas landscapes. Much of that positive outlook has to do with native plants, from hope for widespread prairie restoration to discussing natural solutions such as “living shorelines”: reinforcing degraded coastal areas by planting Spartina spp. and sea oats (Uniola paniculata) rather than pouring more concrete. Though Todd does express concern about coastal marsh restoration, noting that, due to climate change and sea levels rising, “The coast is going to be moving faster than you can get marsh [plants] well established.”

Both he and Ogren are particularly upbeat in regard to prairie restoration, something the Wildflower Center is a major proponent of in both rural and urban settings. Regarding the former, Todd sees a host of advantages to diverse native grasses. A cattle rancher himself, he says, “There are reasons to do intensive rotational grazing aside from bringing back prairies. You can get more cattle … per acre. You have better response abilities to drought and floods. There are lots of things where prairie restoration can be an ancillary, collateral kind of benefit.” He also notes that rural land is often purchased for recreational uses that benefit from maintaining healthy prairies, such as hunting and birding. “If you can bring back prairie grasses,” he says, “you’re going to see meadowlarks and you’re going to be able to shoot quail and dove.”

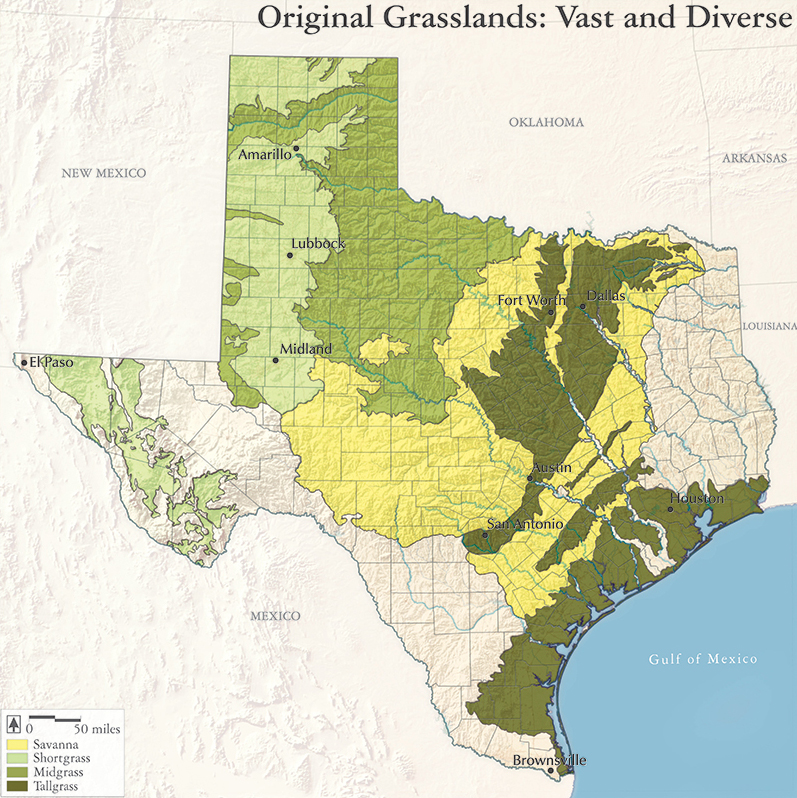

Ogren adds that Texas’ changing population dynamics — the major shift from rural to urban — mean that Texas prairie that was previously cut into tracts for farming or ranching could now be consolidated, a phenomenon that is already beginning to happen in rural areas where “folks are interested in this stewardship idea, how they can bring native flora and fauna to their property.” It’s this sort of changing attitude in landowners that could lead Texas back toward prairies that mimic the ocean in their vastness, a notion echoed in historic quotes opening the book’s section on Prairies, Pastures, Cropfields, and Lawns. “I would love to see an ocean of prairie in Texas,” says Ogren a bit wistfully.

And that ocean doesn’t have to reside only in rural areas. Much like the Wildflower Center encourages planting a pocket prairie in your own backyard, Todd and Ogren see room for native grasses in cities as well. In fact, they note that many municipal weed ordinances have fallen by the wayside in favor of drought-tolerant natives and erosion prevention. “It’s an aesthetic thing,” says Todd; it has to do with where people see beauty. Where that used to be in well-manicured, bright green, short-cut turfgrass, people are beginning to appreciate the look and benefits of a new type of lawn. “A paradigm shift is happening,” says Ogren.

This Texas map, from the book’s Land section, “highlights the state’s original immense grasslands” — in other words, an ocean of prairie. MAP Jonathan Ogren

The Perspective

The authors’ positive attitudes also have to do with seeing negatives not so much as problems but as opportunities. When discussing the fact that Texas has very little public space dedicated to conservation (less than 2 percent), Ogren notes that, over the last few decades, the land trust community has “really started working with private landowners and municipalities and putting more and more land in conservation.” He asks, “If we move forward another 30 years, what does that look like if that trend continues? It’s a really interesting and positive Texas model.”

In the face of one of the most discouraging topics around — invasive species — Todd sees opportunities for education and citizen science. While he recognizes invasives as a big concern, saying they cause an “out-of-body strange experience” for both people and wildlife, he is hopeful that resources like Texas Invasives (which is maintained by the Wildflower Center) will empower people to identify and remove non-native species from their own backyards. In his words, The Texas Landscape Project “celebrates the value of monitoring the natural world. The cumulative aggregate impact of that is gigantic.”

As a longtime volunteer at Blunn Creek Nature Preserve, Todd has also witnessed the cumulative impact of volunteer work and educational outreach. The preserve’s land was occupied by a dairy farm in the ‘40s before being bought for development and left fallow; in other words, it went through long periods of abuse and neglect, resulting in a lot of invasive ligustrum and chinaberry. “At one point it got up to 85 percent ligustrum as far as canopy — very heavy infestation,” Todd says. As a result, very little groundcover was able to grow underneath, meaning rainwater ran right off the surface.

He’s seen thousands of volunteers come through over the years, helping to pull out invasives and replant native grasses. Now, there’s more water being captured, and the creek runs through the summer. “I think there’s a connection,” says Todd. “My belief is that the hydrology of the park really changed because of removing the ligustrum and putting in natives.” And he says building awareness is part of that change.

“We want you to be aware that invasives are an issue, so when you go to Home Depot you don’t buy ligustrum,” adding that you totally can: “A quarter mile from this preserve, there’s a Home Depot where they sell ligustrum.” While that’s not the most encouraging detail, there is hope and power in collecting and sharing information — which is exactly what Todd and Ogren’s book does.

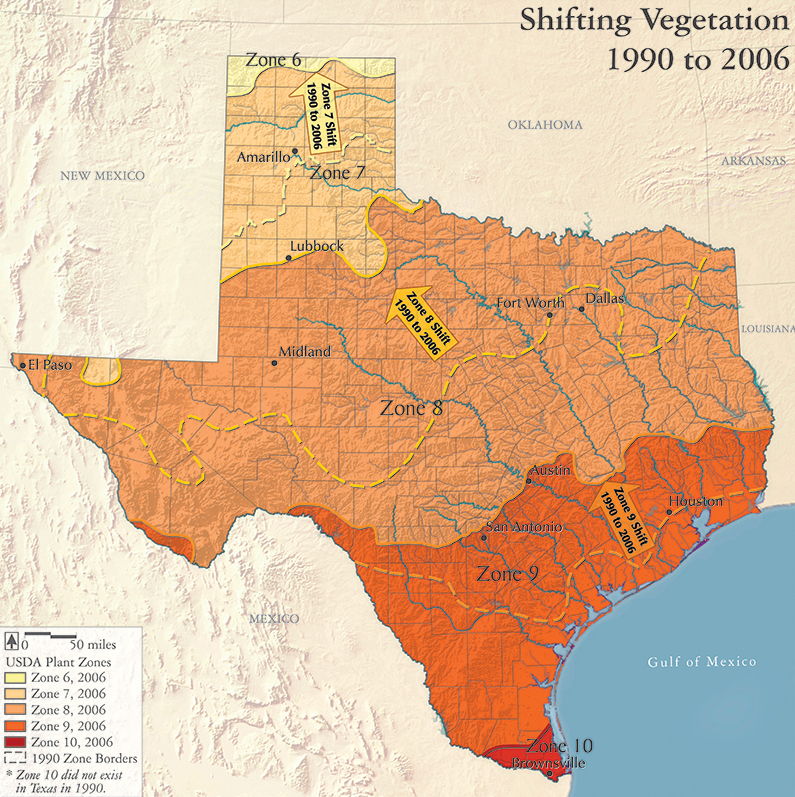

Ogren quotes a favorite saying of Todd’s when he says, “I don’t mind being on the cutting edge, but I don’t want to be on the bleeding edge.” That delicate approach was part of their thought process when addressing a complex topic like climate change: “This image allows us to understand there is a major shift happening in our state,” says Ogren, “and it does have implications for things as simple as what we can grow in certain areas. And if that’s the case, how do we think about the other implications? And there are a lot of them.” MAP Jonathan Ogren

The Future

Todd has learned from this work is that “what really seems to touch people is what individuals did. Sometimes it’s so few people…and they didn’t know they were doing something huge at the time.” On that topic, both he and Ogren reference Lady Bird Johnson more than once.

Todd mentions Mrs. Johnson’s influence in the work he’s seen done at Blunn Creek. “People come through there volunteering their time and sweating and getting heat stroke to pull out invasives and plant natives, and they’re kind of nameless in many cases. They don’t ask for credit or pay,” he says. “And a lot of them you can trace back to Lady Bird. She really made this a visible topic. We owe her a lot.”

Ogren adds that she was “pretty politically savvy” in her influence. “The reason she used the word ‘beautification’ was because she knew at the time it was acceptable. She might have been interested in ecological restoration way back when, but she knew what people were able to hear at that time, the idea of beautification. That’s the inroad. You can tell that more complex story when people are ready to hear it.”

Ogren also highlights her role in beautifying what we now know as Lady Bird Lake, which he calls “this amazing natural area in the center of the city that people are still stewarding.” He says conservation is a long story, and Austin is no exception: “Folks came to Austin in 1839 to figure out where the new national capital for Texas should be, and they talked about this amazing landscape, amazing woodlands, the beautiful waters of Shoal and Waller Creeks, and the beautiful bottomlands along the Colorado River. By the 1860s we had already degraded most of that: the soils, the flora and fauna; people were talking about erosion issues, not enough forage for their cattle. Then fast forward to 1962, and Rachel Carson used Town Lake as one of her case studies in ‘Silent Spring.’ Move forward another decade, Lady Bird, along with [Roy and Ann Butler], decided that they wanted to beautify Town Lake. This [book] is just a snapshot of what’s going on right now, and I think there’s both positive and negative stories within that. And that’s the case over and over and that will be the case for decades to come.”

The great thing, Ogren says, is to recognize that these are dynamic, not static systems. “We can all participate in what happens next. How do we steward it to the next level? That’s a pretty exciting way to think about it.” We at the Wildflower Center couldn’t agree more.

David Todd and Jonathan Ogren have dedicated their professional lives to the environment. Todd has worked as an environmental lawyer and is the founder and executive director of the Conservation History Association of Texas, a small, Austin-based nonprofit dedicated to environmental education; he is also the author (with David Weisman) of “The Texas Legacy Project.” Ogren teaches in the Community and Regional Planning Department at The University of Texas at Austin, has worked for Sequoia National Park, NASA and the Wildflower Center, and is the founder and principal of Siglo Group, a firm that helps clients integrate natural systems into land planning and design (and often collaborates with our own ecological design team).