Botanizing on the Banks

The weather forecast was perfect for a day in the field: highs in the 60s, light winds, no rain, cloudy all day. Hunting season had ended two days before. This meant we could comfortably hike pretty much all day without being too hot, too cold or too wet — and without getting shot. No mosquitoes either. And the rattlers, we hoped, would still be snoozing in their dens on this first day of March 2017. We set out in jet boats for an hour-and-a-half trip 30 miles up the Rio Grande to our westernmost study site, an “X” on the map. Amistad National Recreation Area encompasses the lower reaches of the clear-flowing Pecos and Devils Rivers in addition to a sizeable portion of the Rio Grande. Lake Amistad, the second largest lake in Texas, was created when the Rio Grande was dammed downstream from those confluences in 1969; it was given the name “Amistad” (Spanish for “friendship”) because the lake was meant to serve the water needs of both Mexico and the United States.

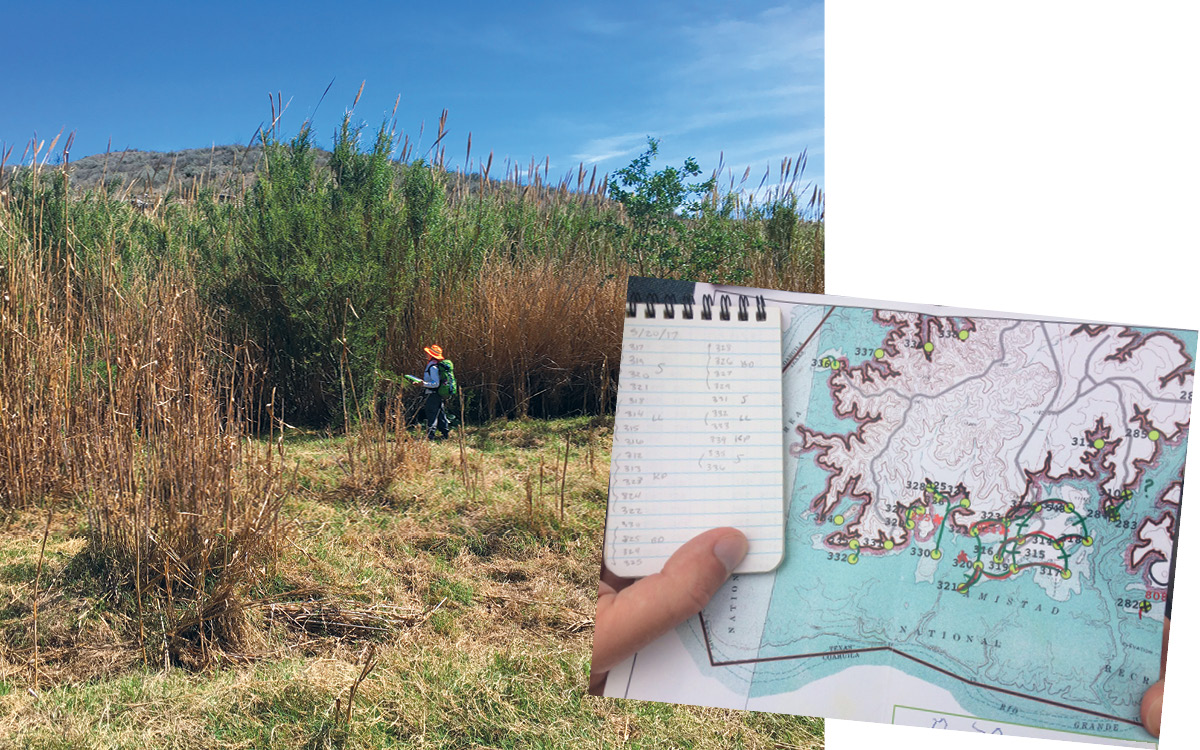

LEFT Wildflower Center Plant Conservationist Minnette Marr is dwarfed by towering invasive cane Arundo donax. PHOTO Karen Clary RIGHT A map showing study sites at Amistad National Recreation Area. PHOTO Stephen Scace

Our task was to survey and map vegetation at the recreation area. Study sites (806 of them) had been selected by members of the National Park Service Vegetation Mapping Program and the U.S. Geological Survey; we managed to survey 560 of them. (The Center has also mapped plants at Padre Island National Seashore, Big Bend National Park, Guadalupe Mountains National Park and Big Thicket National Preserve.) Besides filling the need for a map that identifies where plant communities grow, these maps are vital for planning, vegetation management and resource protection, including the management of invasive plants and protection of rare and endangered species.

The Rio Grande was mesmerizing. It snaked through vertical cliffs of mottled limestone, which reflected every nuance of sunlight and shadow. A gallery forest of ash trees, just starting to leaf out, anchored the soft, sandy riverbank. Near-impenetrable stands of invasive giant cane (Arundo donax) grew alongside the gallery forests, competing for a foothold on the bank. The Mexican side looked no different from the U.S. side — except that it was on the left as we flew upriver. We saw no one else, human or animal, save cliff swallows and hawks on this stretch of river. Along the way, we botanists took mental notes on familiar plant species as well as those that were new to us. Our tech staff monitored GPS units and maps, getting a feel for the river and checking off data points we would come back to later.

All aboard! Researchers approach a boat landing at Amistad National Recreation Area. PHOTO Hans Landel

The boat ride was bone-jarring. We sat on the metal floor of the boat, and our bottoms slammed into every wave. Our daypacks quickly became seat cushions and we scared up extra life vests to lean against. The pilot, a Park Service ranger, steered standing up, an assault rifle racked on the console beside him. His job was twofold: transport and security. He was tasked with keeping a close eye on us, especially when we ventured near known contraband crossings. Twice a day, a fully armed pair of U. S. Border Patrol agents trolled the river in an air boat, scouring the banks for visible signs of recent border crossings. Later on, we found black trash bags on game trails where migrants traversing the river had left behind worn out clothing.

When the boat got as close as it could to the first study site, two team members hopped onto the bank, set their GPS units on the location inland, and slipped into the giant cane stand to find it. (We quickly learned that the cane breaks were much longer than they were wide; it made no sense to go around them.) Once at a study site, our team used standard protocols to identify, record and photograph dominant plant species in circular plots (each of which has a radius of about 31 yards).

We motored downriver about 500 yards, and the next team hopped out and made their way through a thicket of poverty weed (Baccharis spp.) to the next study site. Our pilot leapfrogged back upriver to pick up the first team. And so it went for the rest of the field season from March to May.

None of us were prepared for the grandeur of the spring bloom at Lake Amistad.

Our study sites were scattered throughout the 17,820 acres above the waterline, some a few feet away from the shore, others a mile or two upland. The lake is walled in by cliffs surrounded by private land with few public roads. So we used the water as a roadway. Amistad’s Park Service staff had our backs the whole time — supplying boats and, most importantly, institutional knowledge of the area that was essential to getting the job done. On reaches of the Pecos and Devils Rivers that were too shallow for even at-bottom jet boats, they guided us in kayaks and canoes. On the lake, they ferried us in a 28-foot cabin boat powered by a pair of 225-horsepower outboard motors. They made a carefully coordinated effort look easy.

TOP LEFT A canyon touched by sun, shadow and flowers. BOTTOM LEFT Button cactus (Epithelantha micromeris) displaying reddish pink fruit. ABOVE A foggy morning walk to a study site. TOP RIGHT Walking up a side canyon to a study site. BOTTOM RIGHT Scarlet muskflower (Nyctaginia capitata) in bloom. PHOTOS (clockwise from bottom left) Karen Clary, Jack G. Johnson/National Park Service, Hans Landel, Karen Perez, Hans Landel

Where the water ran out, we hiked up side canyons, some with rock shelters bearing traces of Lower Pecos rock art and fire-blackened ceilings left by prehistoric hunters and gatherers who lived here as early as 4,000 years ago.

According to Texas botanist Jackie Poole, the plant species in the recreation area make up approximately 10 percent of the state’s floral diversity. However, like much of Texas, the land has felt the effects of hard grazing and the relentless advance of invasive species. An invasive species odd couple, lilac chastetree (Vitex agnus-castus) from the Mediterranean Basin and tree tobacco (Nicotiana glauca) from South America, proliferates along the shoreline in spite of attempts to control non-native species. They likely came from a nursery plant or two growing in someone’s yard whose seeds got away. Invasive salt cedar (Tamarix spp.) and giant cane are well-established, and old world bluestems (Bothriochloa ischaemum, Dichanthium annulatum), Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon) and other invasive grasses have moved in as well.

Despite the presence of invasives along the shoreline, native plants prevailed higher in the landscape. And none of us were prepared for the grandeur of the spring bloom at Lake Amistad. Throughout the field season, we witnessed the desert come alive with one succession of flowering native plants after another.

Blackbrush acacia (Vachellia rigidula) is regarded as one of the thorniest and orneriest plants out there. But in early March, it was covered with fragrant yellow blossoms and humming with bees breaking their winter fast. Shrubby cenizo (Leucophyllum frutescens) abounded on the uplands. Known as barometer plant, it fills the desert with sweet-smelling purple blossoms two days after a rain. Giant stands of retama (Parkinsonia aculeata) and huisache (Vachellia farnesiana) came alive with their spectacular golden blooms.

LEFT Botanist Patty Manning in a field of Mexican hats (Ratibida columnifera). PHOTO Hans Landel RIGHT Ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens) in bloom along the Figueroa Trail. PHOTO Jack G. Johnson/National Park Service

Plants rarely seen outside of this desert and only at this time of year wowed us as we came across them on our daily treks. We saw thorny goatbush (Castela erecta ssp. texana) with lipstick red flowers and buds, delicate Rio Grande stickpea (Calliandra conferta) and yellow desert mallow (Hibiscus coulteri). Guayacan (Guaiacum angustifolium), a desert evergreen, showed its indigo blossoms.

Many of the native plants showcased in the gardens at the Wildflower Center are native to Amistad: We found tulipan del monte (Hibiscus martianus) growing out of bare limestone. Button cactus (Epithelantha micromeris) was in fruit, and Texas lantana (Lantana urticoides) and scarlet muskflower (Nyctaginia capitata) were in bloom. The uplands are home to red yucca (Hesperaloe parviflora), a popular drought-resistant staple of the nursery trade. Ironically, it is a truly rare plant, never having been abundant in its native habitat.

Sometimes we are lucky enough to realize when a perfect moment has found us. For me, there were many such moments on this project. I know it had a lot to do with the enthusiastic, knowledgeable team we had assembled from the Wildflower Center and National Park Service and the satisfaction that comes from a job well done. But it was also the place itself. The canyons, the rivers, the rocks, the plants, the critters, the sky, the clouds, the shadows, the wind, the quiet. They filled me with awe and let those perfect moments come my way.

Dr. Clary served as project director and oversaw five eight-day trips to Amistad National Recreation Area for the Wildflower Center. She retired from her position as the Center’s director of plant conservation in August 2017. Maps resulting from this work will eventually be available to the public at science.nature.nps.gov/im. Learn more about the project here.